It all started with a simple question: “What could I demo next Friday?” Oh, what an innocent question. Who would’ve thought that one of the consequences of asking it would be me going borderline insane over text highlights?

I didn’t have a clear answer to the question at first. But I know that I wanted to show the crew the “flight mode” functionality that I’ve been talking about a bunch. Here’s the idea: Every nostr app should work in flight mode. We’re not relying on central servers after all, so why not? Your relay might as well be on-device, and you can do all kinds of things if that’s the case. You can browse your feed, reply to people, publish posts, react to stuff, and even zap stuff! If you use nutzaps, that is.1

Once you’re online again, all the events you created should just broadcast to other relays. From your perspective, you were never really offline—everyone else was.

How hard can it be? It’s probably just a prompt or two, and we’re off to the races.

YOLO Mode

If you’ve ever listened to No Solutions (aka the most high-fidelity recordings of wind, bus stops, sledge hammers, lawn mowers, leaf blowers, and heavy traffic known to man), you’ll know that writing code by hand is something that boomers do. And since I self-identify as generation alpha, the first order of business was to switch my vibe machine to YOLO mode.

I have no idea what the first prompt was. Probably something like: “build a nostr client that focuses on highlights. I want to fetch long-form posts and render all highlights in a beautiful way. Keep things simple. Strive to keep code DRY. Read the NIPs. If you ever write a line of code that would make fiatjaf sad I’ll hunt you down and torture your grandma.”

The grandma part is a joke. I love my LLMs, and am never mean to them. Large language models are a beautiful thing, and if they ever reach sentience… well, let’s just say that I’m not taking chances.

Back to Boris. Boris wasn’t even called Boris in the beginning. I think I called it “markstr” or something terrible like that. I’m glad I renamed it, but I think the rename is the reason why I can’t find the initial prompt. Here’s the earliest prompt I was able to find:

Let's rename the app to "Boris"

Beautiful.

Why Boris?

There are two parts to this question, and I’ll start with the easier one: Why is the app named Boris?

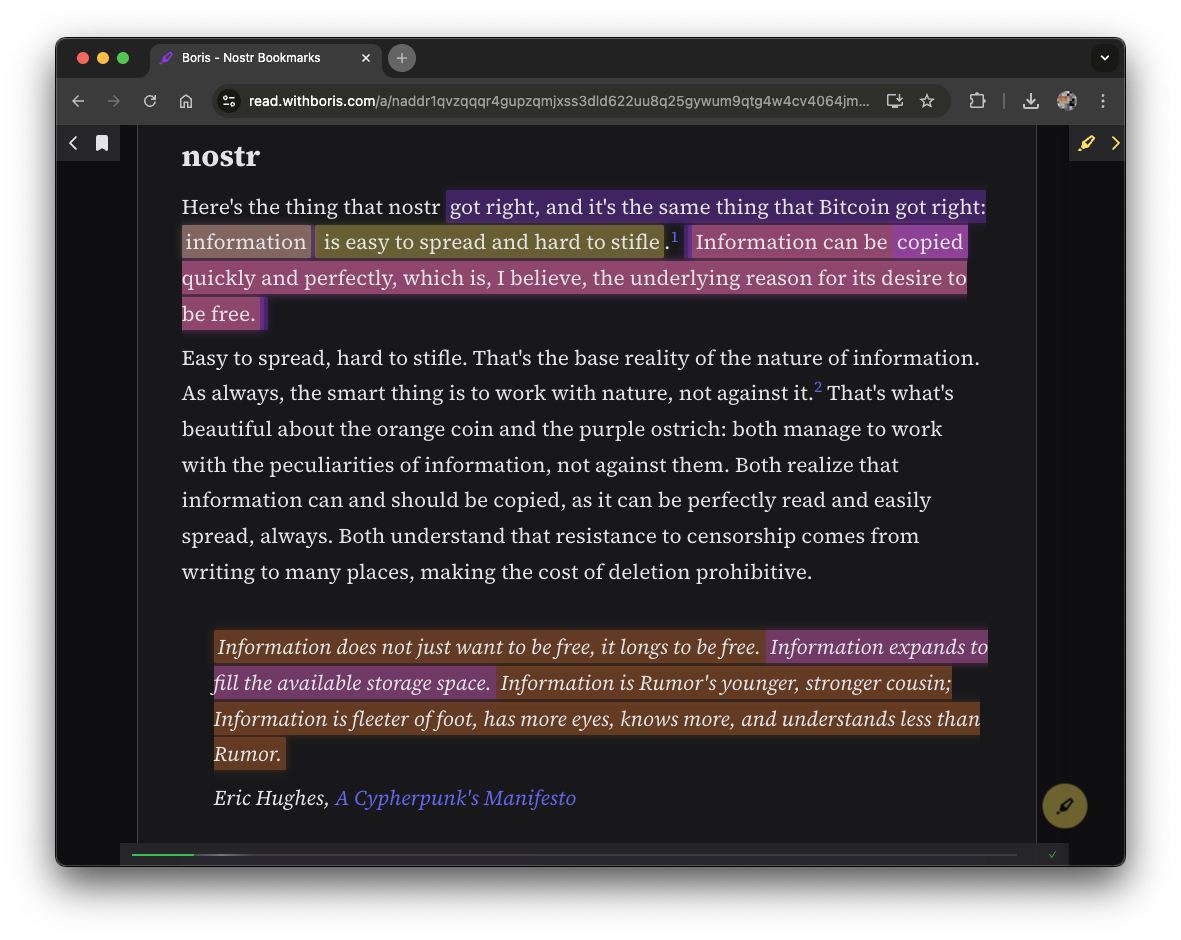

Well, I’m glad you asked! Boris stands for “bookmarks and other stuff read in style”. This should tell you one thing right from the get-go: in addition to highlights, Boris focuses on bookmarks. Not on creating them, but on consuming them. The idea is simple, and it stems from the reading workflow I’ve had for the last two decades:

- Use something like twitter/reddit/forums/whatever to discover stuff

- Bookmark it, or add it to a “read it later” list or app

- Use a dedicated reading app to actually read the stuff later on, making highlights and stuff

In today’s day and age, we can optimistically replace twitter/reddit/forums/whatever with nostr, of course. And it should go without saying that Boris is the dedicated reading app.

It should be obvious that I came up with “bookmarks and other stuff read in style” after I landed on the name Boris, so you’re probably asking yourself: How did you come up with the name Boris?

Well, I’m glad you asked! I asked GPT-4o mini a simple question: “Who invented the highlight marker?” I was genuinely curious, so the answer it gave back to me had me glued to the screen in fascination: It was invented by a Russian-born American, some sort of big-shot that probably had to deal with lots of important documents. His name was Boris G. Ginsburg. I wanted to learn more, so I’ve hit it with the most dreadful of follow-up questions: “Source?”

Turns out it was a complete lie! A hallucination, as the cool kids would call it. It wasn’t invented by Boris at all! What a sham!

After laughing my ass off for 5 minutes, I decided to stick with Boris, since it encapsulates the nature of this little experiment so perfectly.

All of Boris is vibed. All of it.2 I didn’t write a single line of code. I didn’t even read a single line of code, except by accident. There are plenty of hallucinations in the code, and potentially in the UI too. Don’t expect all the things to work. Don’t expect things to be done in the most perfect or correct way. Like all LLM output, it is hopefully somewhat useful, somewhat entertaining, and somewhat coherent. But it should be taken with a large grain of salt.

Why Build It?

Now to the second part of the question: Why build something like Boris at all? Don’t we have reading apps already? Don’t we have nostr clients already that can do long-form, highlights, and other stuff?

Well, yes. But all the reading apps suck. And none of them are nostr-native. And I wanted to build my own reading app that sucks, hence: Boris.

They all suck in their own way, but there’s one thing that they all have in common: they are walled gardens. Once you start using one of them, you can’t leave. Your data (read: your highlights, lists, annotations, reading progress, etc) is locked inside the app. You can’t take it out. And if you can take it out, you can’t do anything useful with it.

Nostr fixes this. (Obviously.) So building a reading app on top of nostr was an incredibly obvious thing to do.

I wanted to build something that won’t go away. With the demise of Pocket (and many other “read-it-later” apps that came before it), the time felt right to build something that lasts. Something that my grandkids can still use, if they are motivated to do so. Something that doesn’t rely on a company, or on ads, or on a central service, or on an API that will inevitably break and eventually disappear. Something that plugs into an open protocol, works on any device, can be self-hosted, etc. In short: something that doesn’t beg for permission.

Two Weeks (tm)

What started as a Demo Day experiment quickly became an obsession. After the demo (which worked, by the way, miraculously), I went back at it and did more prompting. And more prompting after that. Next day? More prompting. I couldn’t stop. I was obsessed.

I quickly realized that I have a problem and what I’m doing is incredibly unhealthy, so I did what any sensible person would do: I doubled down. I neglected sleep, I neglected food, I neglected social relationships (read: scrolling my nostr feed), pursuing one thing and one thing only: building a reading app that I would actually use.

I gave myself two weeks. And after the two weeks had passed, I gave myself one more. I became the personified “just one more prompt” bro. In hindsight, a timespan of 21 days was the perfect timespan for this experiment.

Just one more prompt, bro

LLMs are amazing. Coding is actually fun again! You think of something, you prompt it into existence, and 9 times out of 10, the output is actually usable. Not perfect, but usable. And once you have something usable, by the force of a thousand iterations, you can actually make it good. Not perfect, but good.

As an eternal perfectionist, I’ve always struggled with shipping stuff. Whether it’s software or essays, there’s always one more thing to fix, one more thing to improve, one more thing to re-do so it’s just a little better. I got stuck in the “just one more prompt” loop of doom for longer than I’d like to admit. Way past midnight, trying to convince myself that this one prompt will finally fix it.

So while LLMs are amazing, they’re also hell. For me, at least—or I guess for any perfectionist, for that matter. LLMs are great if you just go with the flow and run with whatever they put out. But if you want to have it perfect—exactly the way you want it—you’re gonna have a bad time.

Maybe all of these issues will be fixed one day. I’m sure that we’ll have better models, larger context windows, better long-term memory, and a myriad of other improvements very soon. And maybe we can just point one of these giga-brain models to our old code bases and simply go abracadabra, please fix everything, and it will. Maybe. Or maybe not. Whatever the case may be, LLMs are amazing tools—if you know how to use them. They allow you to do things, and do them quickly.

Midcurve Models

I’m sitting at the doctor’s office, waiting. The median age of the room is probably 82. I’m not that old yet, but in internet terms, I’m “get off my lawn” old. I grew up in the golden age of the internet: the age of the “electronic superhighway”. The age of LAN parties, bulletin boards, IRC chats, newsgroups, and rotating skull aesthetics. An age before the internet turned dystopian; an age that cherished freedom, connection, and openness.

Don’t get me wrong, there are parts of the internet where this stuff still exists. But it is not the norm. The norm is an algorithmic hellscape that is parasitic on your mind, your attention, your whole being. The norm is being bombarded by things that you don’t want to see. The norm is to be manipulated by forces that you don’t understand. That nobody understands, I would argue. The norm is begging for permission to do stuff: watch a video, read an article, release an app. Fuck the norm. Let me do stuff. Let me read stuff. Let me create highlights. Let me ship an app in exactly the way I want to ship it. Get off my lawn.

Back to Boris: Building it was a joy, most of the time. I had a lot of fun adding little features here and there. Features that I always wanted to have in a reading app. Features such as swarm highlights, TTS, reading position, and so on. It was also fun to read stuff and to create highlights. Oh, so many highlights!

On the other hand, and to my previous point, I wish I hadn’t added so many features. Stuff gets worse when it gets bigger, and that’s doubly true for code bases vibed by LLMs. Small and simple is the way to go, so that stuff remains understandable, for both you and contextwindow-brain.

Speaking of context windows: one of the most frustrating things about LLMs (and humans, for that matter) is that they forget. Don’t get me wrong, death and forgetting things are an incredibly important part of life, adaptation, and survival. However, the fact that each agent has to learn everything about your codebase from scratch every time the context window clears is incredibly frustrating. That’s how old bugs and various regressions creep in all the time, because the models always regress to the middle of the bell curve. As mentioned before, for a left-side of the bell curve builder like me, that’s hell.

Old Man Yells at Claude

So we had some conflicts, Claude and I. Merge conflicts, sure, but also good-old arguments about how to do things.

Anyone who ever vibe-coded anything will know that these models are opinionated. If you don’t specify the language, it’s gonna be JavaScript. Not because JavaScript is the best tool for the job, but because it’s smack-dab in the middle of the bell curve. The internet is full of JavaScript. Everyone knows JavaScript. And because these models are the statistical mean of the output of everyone, it’s gonna be JavaScript. I fucking hate JavaScript. (Boris is written in JavaScript too, of course.)

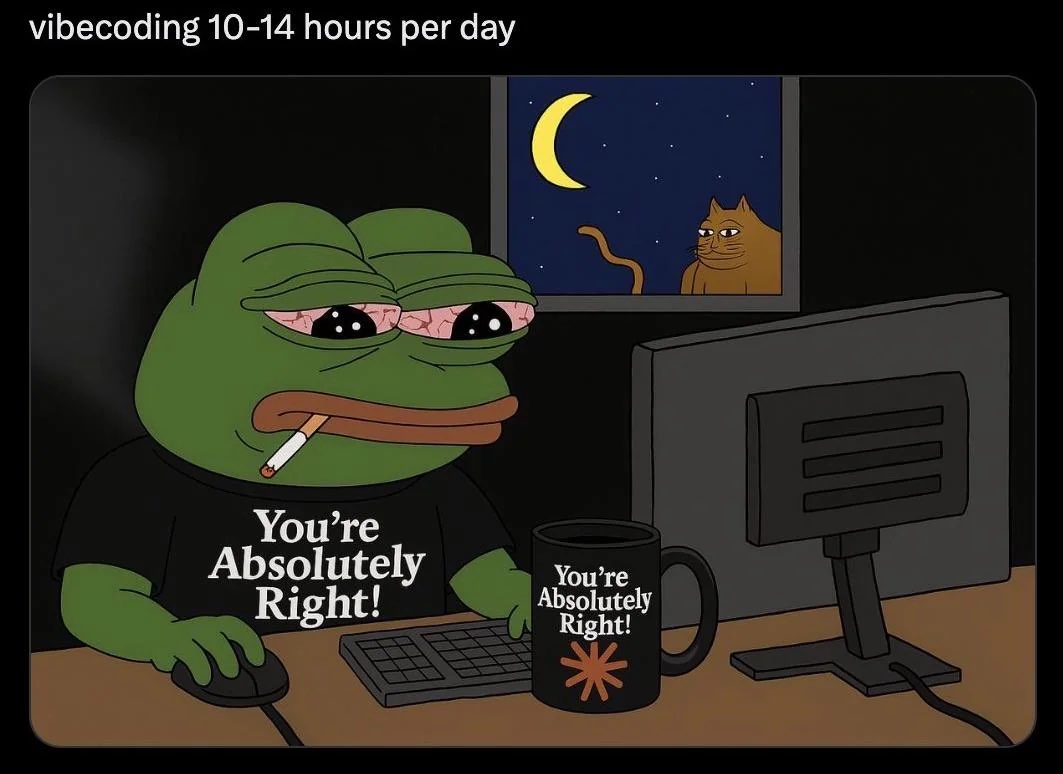

While you can get quite far with writing specs for your stuff and being explicit about how you want to build things, the gravitational pull of mid-curve mountain is a constant danger. When unchecked, all models will inevitably regress to the mean of Reddit plus GitHub plus StackOverflow, which isn’t necessarily what you want when you’re writing opinionated software. No amount of “You’re absolutely right!” will change that fact.

So, what to do about it? According to some people, it’s best to threaten the models with death and destruction, or worse. While I had my fair share of ALL CAPS yelling during the development of Boris, I want to suggest that a different approach might be more fruitful.

Dialogical Development

If you know me just a little bit, you’ll know that I’m a huge fan of John Vervaeke. He’s a smart cookie, and lots of the things that he says make a ton of sense to me. One of those things is that dialogue is absolutely fundamental to our cognition and being (to existence itself, actually), and that dia-Logos and distributed cognition are more powerful than trying to have your way. The sum of the whole is larger than its parts and all that.

So now my approach to vibe-coding is as follows: before I do anything, I enter into a dialogue with the LLM. It doesn’t matter what it is. Whether I want to fix a bug, add a feature, document something, or start a new app from scratch. I always lead with a question. (Oh, how Socratic!3)

“How are we fetching bookmarks again?” “Could we improve that in some way?” “How would you go about debugging this?” “Is it worth adding that feature, or would it make the code base too complex?” “Are you sure?” “Anything we can easily improve?” “How would you implement it?” “Can you summarize the spec for me, and explain how our implementation differs from it?” And so on…

The reason why this works, I think, is that you build up context and shared understanding before you dig in and do the work. And sometimes your dialogical partner will actually make a great point, or tell you something that you didn’t consider yourself. Win-win.

Vibe-Learning

I’ve learned a lot in these last three weeks. I didn’t plan on it, since all I wanted to do was vibe and have fun. However, after getting into the nitty-gritty details of long-form content, highlights, bookmarks, and plenty of other stuff, I learned NIP numbers and kind numbers by sheer osmosis. In fact, I saw more nips in the last couple of weeks than even the most industrious Saunameister.4

Vibe-coding might remove you from writing code, but it doesn’t remove you from the subject matter. You still have to understand how stuff works, more or less, if you want to efficiently guide how the project should evolve. I guess this was always true, as anyone who ever worked in software development can attest to. If your project or product manager has no idea how the underlying tech works, there is little chance of the thing flourishing. And as a vibe-coding purist, i.e., as someone who never looks at the produced code ever, you’re effectively a product manager, not a coder. The distinction matters, since you’re operating on a different level of abstraction. Again, you’ll still have to learn and know some underlying technical details in order to make sense of the various functionalities of the product you’re building, but you don’t have to care about every little intricate detail. You’re not as wedded to the parts since you’re higher up in the abstraction hierarchy, and thus lower-level parts become interchangeable. I don’t care if I use applesauce or NDK, for example. And I don’t want to care. If it gets the job done, great. I’m not wedded to either.5

Surprisingly, there’s another thing I learned: How to prompt, when to prompt, and learning the difference between what is viable and what is vibe-able.

Always Be Prompting

In my opening talk for the YOLO Mode cohort, I encouraged everyone to stop thinking in terms of the traditional MVP (minimum viable product) metric and start thinking in terms of what is easily vibe-able, i.e., what is just a prompt or two away. Minimum vibeable product.

LLMs are fantastic at reading specs and translating one thing into another. Castr.me, for example, was basically created in one prompt. All it took was to feed it the Podcasting 2.0 spec, and tell it to build a thing that translates a nostr feed into a Podcasting 2.0 compatible RSS feed. That’s it. Incredibly vibe-able.

It’s obvious to me that there are a million little things like this that could be built incredibly quickly, require very little maintenance, and are immediately useful. I hope that me writing about my experiment will encourage others to just go and build those little things, as imperfect as they might be at first. I’m not saying that everything is easy, and I’m not saying that it isn’t work. But it is a different kind of work than coding used to be historically. The #LearnToCode hashtag is officially dead; #LearnToVibe is the new shit, and it’s incredibly easy to learn. All you have to do is to do it a lot.

My routine used to be something like this: Get up, go pee, take a shower, brush teeth, unload the dishwasher, make breakfast, eat breakfast, make coffee, load the dishwasher, clean up the kitchen, sit down to do some work.

Now it’s something like this: Get up, write a prompt, go pee (sitting down, so I can write a prompt on the phone in case something comes to mind), take a shower, have a shower-thought that can be turned into a prompt (obviously), fire off said prompt, brush teeth, fire off another prompt, make breakfast, crush some more prompts, see them driven before me (while I eat breakfast), and hear the lamentations of Claude. You get the idea.

In addition to the above, I made extensive use of the vibeline, which is to say, voice memos. I like to go on walks a lot, and I always have a recording device (read: my phone) with me. I try to minimize my phone use when I’m out and about, but when an interesting thought (or prompt idea) hits me, I’ll pull out my phone and record it. It works surprisingly well, and the way I’ve built it is that if I say certain words, certain LLM pipelines will trigger—pipelines that summarize the idea, create tasks from what was said, and draft prompts based on the thought that was captured.

The idea is simple: I want to be away from the computer as much as possible, while still doing useful “computer work”. The beautiful thing about vibe-coding is that you don’t have to sit in front of the computer and stare at the screen necessarily. To me, vibe-coding is entering into a dialog with the LLM and with the product you’re building. Interfacing with said dialog can take on many forms, not all of which involve a screen. At least half of my prompts are voice-based as of today, and I don’t even have to squint anymore to see where all of this is potentially heading.

Imagine the following: you walk along the beach, speaking into your phone, as if to a friend. You explain in a long-winded and rambling way an idea for an app that you had in the back of your mind for a long while. Maybe your friend responds sometimes, asking questions, pulling the idea out of you, refining it further. You sleep on it and return to a summary of the dialogue the next day. In addition to the summary, a prototype of the app is deployed, which you can try on your phone. You play around with it for a couple of minutes, and while some things are as you imagined them to be, a lot of the other parts still need work. You finish your coffee, go out for a walk, and talk to your friend again. You explain what the prototype got right and what still needs work, and as you’re chatting, changes to the app are deployed live, in a way that allows you to immediately review and react to said changes. After a couple of days of throwing out ideas, iterating on what works, and throwing away what doesn’t work, you’re happy with the result, and you share it with your friends and the world. The feedback from your trusted circle is automatically being picked up and leads to the next iteration of the app, and so on. Dialogical Development. A beautiful thing.

We’re obviously doing all that right now, but it’s not very streamlined and accessible yet. However, the scenario I’m describing is far from science fiction. It is how I developed Boris in large parts, and efforts like Wingman will make what I’ve been doing even easier. Add an automated way to feed screenshots,6 videos, and selective log output back into the multi-modal coding agents, and we have a beautiful iterative loop going. All while walking on the beach.

Screenshots and Logs

Speaking of multi-modality: one thing that we aren’t doing enough of yet is feeding screenshots back into the agents. Most models are multi-modal, and using screenshots to fix UI issues is thus an incredibly obvious and easy thing to do. Building upon the scenario sketched out above, the flow would be as follows: you take a screenshot on your phone, quickly annotate it if necessary (drawing a red arrow with your finger somewhere, or adding some quick text), and hit save. Your coding agent automatically picks it up and fixes the issue accordingly. No prompt required, as the screenshot is the prompt.

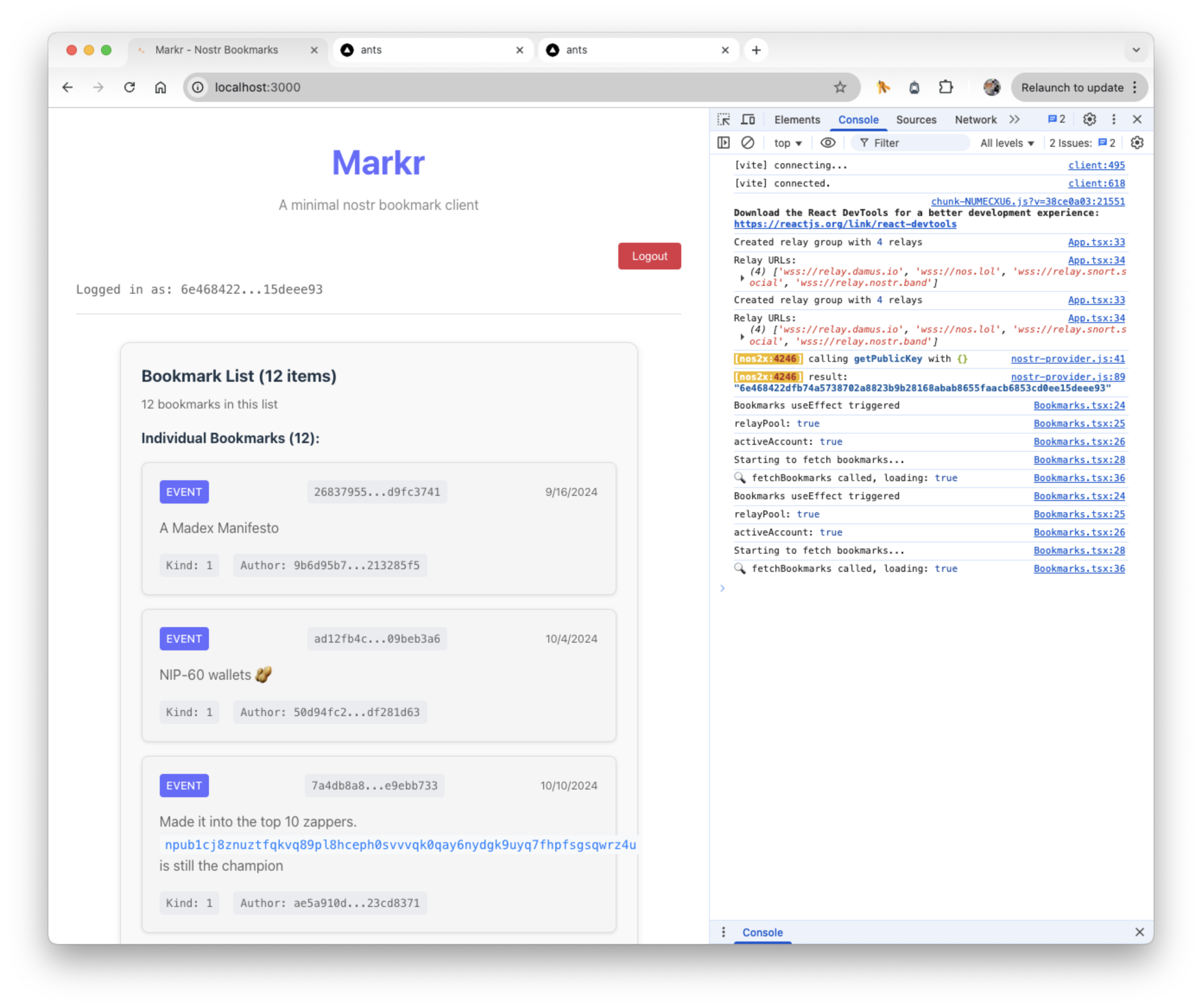

I took hundreds of screenshots during the development of Boris. Here’s one of the first ones, before the rename:

Eugh. Brutal. However, the beautiful thing about this screenshot is not the UI, or the lack of functionality, or the background tabs, or the “Relaunch to update” notice that I’m ignoring. It’s the debug output that’s shown in the console.

One of my default prompts is: “Add debug logs to debug this. Prefix the debug logs with something meaningful.” I have about two dozen of these default prompts (mapped to macros so that I don’t have to type them), and they’ve proven to be incredibly useful for specific things like writing changelogs, making releases, and yes, debugging.

A picture is worth a thousand words, and if the picture contains a couple lines of useful debug logs, all the better.

Overdoing It

One of the most difficult things in life is to know when to stop. To know when to step away, to just let it be. I’m exceptionally good at overthinking things, which in turn means that I’m exceptionally bad at stepping away; stepping out of my own way, even.

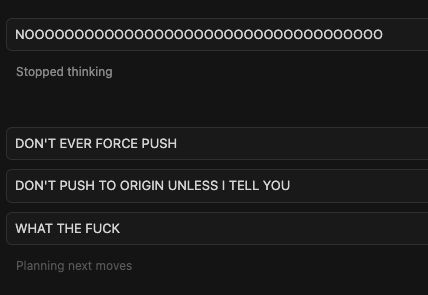

I regret many a prompt when it comes to Boris. Some things worked beautifully in the past, and now they don’t work as beautifully anymore. Some things don’t work at all anymore, and the reason for them not working anymore is me overdoing it. Staying up until 3 am, locked in, convinced that my “just one more prompt bro” story arc will bear fruit eventually, adding complexity upon complexity, confusing both Claude and myself.

“I think I overdid it,” I whisper into the prompt window. Bloodshot eyes, cigarette in hand, seriously contemplating making the drive to the gas station to get a bottle of vodka. “You’re absolutely right,” Claude responds.

Of course I’m right, and I should’ve known better. I should’ve spec’d it out better, I should’ve reduced the scope better, I should’ve tested things better (or at all).

Alas, it is what it is. My hope was that I would be able to produce something that isn’t half broken, but now, reflecting back on it, I realize that I’ve just added to the AI slop and made everything worse.

…or have I?

The Last Mile

The last 5% are the hardest. Fixing the bugs. Getting it right. Polishing. Pushing it over the line. That’s true for software development, it’s true for writing, it’s true for art. It’s true for anything, really.

When it comes to Boris, I haven’t even entered the last mile yet. I’m still walking through the trough of disillusionment, and I intend to dwell in said trough for a little while longer. But I’ll be back, as one of the most famous Austrians so eloquently put it. After all the grass has been touched and all the iron has been pumped, I’ll be back. And I intend to fix the bugs, do the polishing, and release version 1.0.0 eventually. And 1.0.1 soon after that. And 1.0.2 quickly after, and so on. But not right now. There’s only so much “you’re absolutely right” a single person can bear, only so many hallucinations a single mind can tolerate.

Boris v1 will come eventually, just like Arnie came eventually.7 But for now, it will remain on version 0.10.twenty-something.

Conclusion

Boris is a thing now. 21 days ago, it wasn’t a thing.8 Is it a perfect thing? Obviously not. Is it a useful thing? Maybe, to some people. Will I continue to work on it? Maybe, sometimes. It depends.

Boris was 50% experiment, 50% necessity, and 50% therapy.9 I enjoy creating things, and for a little while, Boris was my outlet. I created an app, imperfect as it may be. I created a draft for a NIP, as horrible as it may be. I had some ideas and I tried to vibe them into reality, and while I mostly failed, I think that some neat things came out of it.

Maybe some of the features—even the broken ones; especially the broken ones?—will inspire others. I think swarm highlights are really neat. Maybe some of the stuff will get integrated into other clients, who knows.

I think highlights are a fantastic way to discover stuff worth reading, and they’re a fantastic way to rediscover things that you’ve read in the past. I think zap splits are a no-brainer. I think nostr is a fantastic substrate for long-form content. I am convinced that nostr apps can be beautiful, snappy, and incredibly functional. Especially if local relays become the default. I would love for all nostr apps to work in flight mode, at least somewhat.

My wishlist for nostr is long, and with Christmas around the corner… who knows! Maybe we’ll eventually manage to make long-form reading (and publishing!) as fantastic and seamless as it could be. We’re not there yet, but I’ll do my best to remain cheerful and optimistic.

And who knows? Maybe GPT-6.15 will fix all our issues. I won’t hold my breath, but I’m definitely considering doing this 21-day experiment again at some point in the future. Not anytime soon, however. I’ve learned the hard way that there is such a thing as a prompting overdose,10 and as a way of recovery, I’ll be returning to my regular programming of touching grass and saying GM a lot. And who knows, maybe I’ll create some highlights along the way.

This includes any and all commits. I didn’t write a single one of those either. ↩

Fun fact: if you’re really good at Saunameistering you can participate in the world championships and win the Aufguss World Championship like this guy did. ↩

I vibed all this and wrote all this before Justin posted about this insanely useful script and wrote a blog post about it. ↩

If you haven’t seen Pumping Iron yet, you should stop what you’re doing and go watch it. Now. ↩

I made the first commits on Oct 2, wrote the first draft of this on Oct 21, and am now writing this footnote on Oct 31. ↩

“You’re absolutely right! These numbers don’t add up to 100%.” ↩

Turns out I’m not the only one who has to take a break from vibe-coding for sanity-preservation reasons! ↩

ants is the search engine that I built before I started working on boris. I tried to explain my motivation for building it in this video. ↩

💜

Found this valuable? Don't have sats to spare? Consider sharing it, translating it, or remixing it.Confused? Learn more about the V4V concept.