We should treat computers as fancy telephones, whose purpose is to connect people. Information is alienated experience. Information is not something that exists. Indeed, computers don’t really exist, exactly; they’re only subject to human interpretation. This is a strong primary humanism I am promoting. As long as we remember that we ourselves are the source of our value, our creativity, our sense of reality, then all of our work with computers will be worthwhile and beautiful.

Jaron Lanier

It turns out that the killer application for virtual reality is other human beings. Build a world that people want to inhabit, and the inhabitants will come.

Charles Stross

There is much to be said about virtual worlds. The “information revolution,” as it is called, has been going on for multiple decades, and it should be apparent to everyone that our world is becoming more digital by the day.

But what does that mean, exactly? Does it mean that things are transforming into something that is less real? Will absolutely everything dematerialize, ourselves included? Is the rapture of the nerds imminent, and only those who praise the gods of the singularity will be saved?1

I hope not. While it is true that software is eating the world,2 we have to differentiate between the digital and the virtual.

Digital vs. Virtual

As any dictionary will tell you, digital is anything that can be expressed as digits, i.e. any information that can be represented in discrete numerical form. In our modern world of binary encoding, that means everything that can be encoded as zeros and ones.

digital, adjective — (1) (of signals or data) expressed in discrete numerical form, especially for use by a computer or other electronic device.

Not everything that is digital is also virtual. A digital radio is not a virtual radio, it just works differently than an analog radio. Once said radio is put into a computer game, however, it clearly becomes a virtual radio.

virtual, adjective — (1) existing or resulting in essence or effect though not in actual fact, form, or name. (2) created, simulated, or carried on by means of a computer or computer network. (3) not physically existing as such but made by software to appear to do so

According to one dictionary definition, virtual is “anything that is existing or resulting in essence or effect, though not in actual fact or form.”3 A virtual meeting room is not an actual meeting room, but it has the effect of one. It is made of bits and bytes as opposed to brick and mortar, but the meetings that are being held in it, the conversations that are being had, and the decisions that are being made, are still real. The space is virtual—what happens in it is not.

As we shall see, digital money can and will emerge in virtual worlds. In fact, it has emerged many times, in multiple worlds and various forms. To paraphrase Charles Stross: build a world that facilitates trade, and money will emerge.

Virtual Scarcity

As we have seen in Chapter 4, humans have used a multitude of objects as money over the millennia: cattle, salt, shells, bones, pearls, stones, copper, bronze, silver, gold, and other precious metals. While the list of historical monies is long, there is one trait that all functioning monies share: scarcity. After all, if something is extremely easy to find or produce, it isn’t good money, or at least not for long.

Digital goods aren’t naturally scarce. The marginal cost to replicate them is practically zero, as anyone who ever copy-and-pasted something can attest to. For this reason, digital scarcity used to be an oxymoron. If something is digital, it is just information, and information can be easily copied.

Before Bitcoin, all digital scarcity was scarcity by authority—authority that can be circumvented or exploited. It was always simulated scarcity. Virtual, not real.

Without the limitations of physics, digital goods necessitate that a central authority regulates the issuance, access, and duplication of said digital goods. If access isn’t regulated, anyone can simply take the information that represents this digital good and make copies of it (or, sometimes even more problematic: change it). It doesn’t matter if it is the bits and bytes that define the balance of your bank account, the books in your Kindle, the movies in your Netflix library, the songs in your Spotify playlists, or the items in your favorite video game. If access isn’t centrally controlled, people will change things to their advantage. They will update the balance of their bank account and modify in-game items to make their character more powerful. In other words: they will cheat. Digital goods are just information, and information wants to be free—as the unsinkable ships of Pirate Bay and endless leaks and data breaches clearly show. Building a cage around information is anything but easy.

To get a better understanding of digital goods and their scarcity (or lack thereof) we will take a look at the virtual worlds that first spawned them: online games.

A Short History Of Virtual Economies

In-game economies are almost as old as networked gaming itself. In 1995, Julian Dibbell published MUD Money,4 which describes how money was introduced in Multi-User Dungeons (MUDs). Coins would appear randomly in these online worlds, so if you stroll around for long enough you would, over time, find enough money to pay for certain goods and services in these games. Randall Farmer, a researcher at MIT who studied the emergence of virtual economies at this time, describes how in a game called Habitat “players could acquire […] funds by engaging in business, winning contests, finding buried treasure, and so on.” He details how players would get a certain amount of tokens every time they log in, and how “they could spend their tokens on, among other things, various items for sale in vending machines called Vendroids. There were also Pawn Machines, which would buy objects back (at a discount, of course).”

Money, gold, points, tokens, and coins are constant companions in almost all games. Come to think of it, most of the games that we now consider classics have money-like objects in their virtual worlds: Mario has his coins, Sonic has his rings, and almost every final boss will drop precious items or heaps of gold once he is slain. In RPGs in particular, no matter what kind of creatures you are fighting, you will probably have to acquire gold to upgrade your weapons and armor.

However, when it comes to single-player games, the digital coins you collect are worthless. But once an exchange is facilitated via networked play, things start to get interesting. Players will inevitably trade the virtual treasures they collected over time, whether there are official trading mechanisms in the game or not. All that is required is that the stuff that is found and sold stays around, i.e. that the shared world is persistent.

If a world is shared and persistent, real money and real economies can emerge. While there are many games that had (and still have) vast virtual economies, I want to highlight three in particular: Ultima Online, Diablo 2, and Second Life.

Ultima Online: Planning a Virtual Economy

Ultima Online was released on September 24, 1997, by Origin Systems. It was one of the first MMORPGs5 that garnered mainstream attention, attracting over 100,000 players within six months. Like the MUDs before it, the world of Ultima Online is a persistent world, which means that your actions and interactions in the game have lasting consequences for yourself and other players. In stark contrast to single-player games or non-persistent multiplayer games, you can not “save” the state of your game and “load” it at a later point. Everything happens in real time, with real consequences for real people. Consequently, the time and effort players put into leveling up their characters and gathering items and resources are real as well, which, in turn, spawn real economies around these virtual goods.

To quote Zachary Booth Simpson who studied the in-game economics of the game extensively: “Ultima Online, and online games similar to it, offer a unique research platform because, while the commodities traded are virtual, the resulting economies are not simulations.”6 Matthew Beller from the Mises Institute echoes this sentiment: “Some economists might dismiss virtual worlds as an application for economics, given that they do not contain any resources that are traditionally considered scarce (lumber, steel, oil, etc.), but a closer inspection reveals that some virtual worlds contain real market economies complete with scarce resources, property rights, entrepreneurship, and exchange.”7

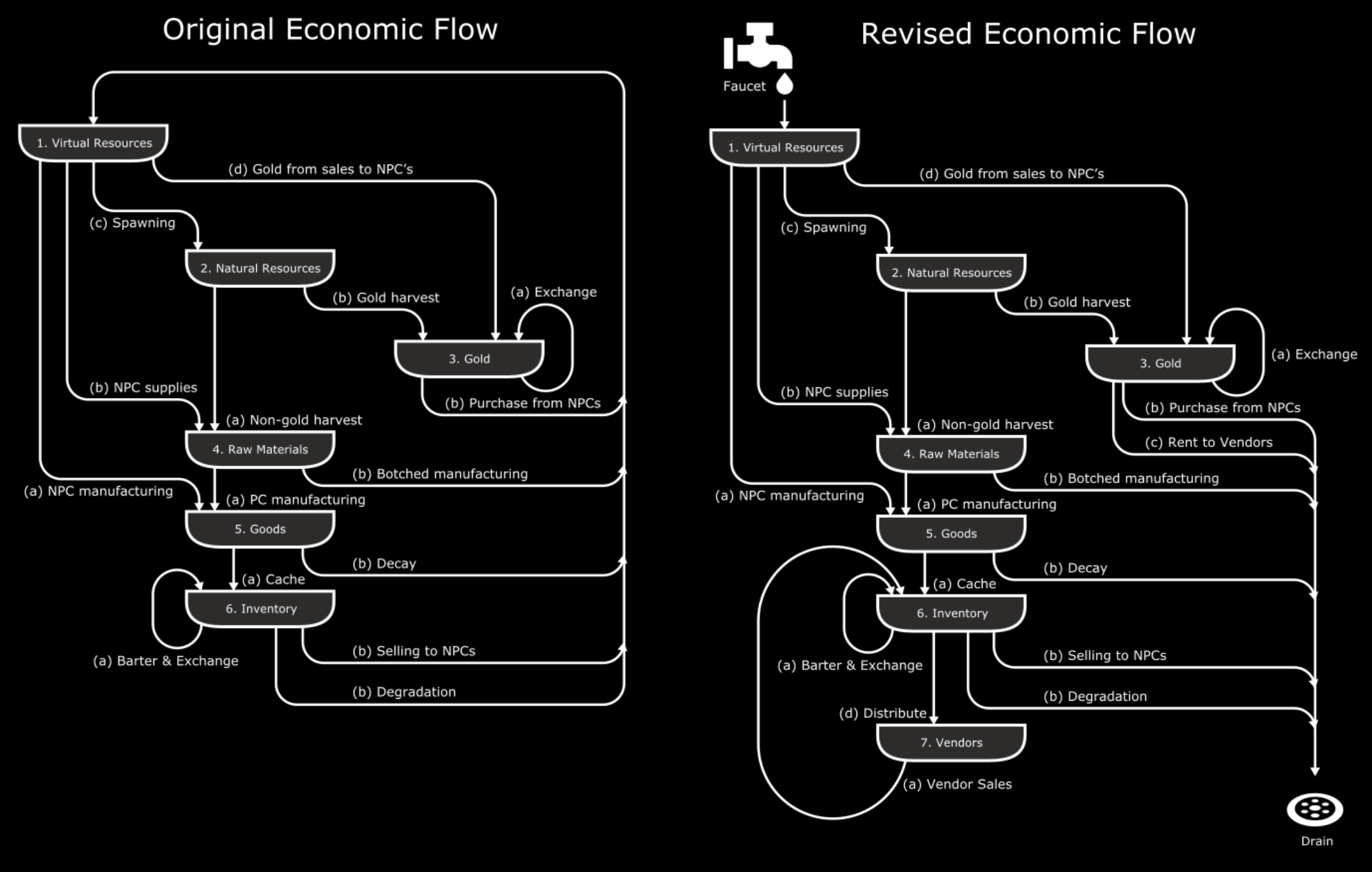

The world of Ultima Online allows for spontaneous economic interaction between players. Players are free to trade as they see fit, directly, without restriction in regards to what to trade or with whom. However, some parts of the game’s economy are planned by the game’s designers. For example, players can sell their goods to NPCs8, receiving gold in return. Also, players can explore the world and harvest natural resources, e.g. hunt wild animals for fur and meat, cut down trees to gather wood, and so on. Naturally, these computer-controlled aspects of the game have to be pre-programmed: how much of a good is an NPC vendor willing to buy, and for what price? How many rabbits spawn in a certain area? How quickly will a forest regrow?

As always, human players were quick to find patterns that could be exploited. To gain the maximum benefit from exploiting these patterns, many players used macros and scripts to automate what would otherwise be tedious tasks. For example, players would automate the production of goods that netted a laudable profit when sold to NPCs, enabling them to earn money while they slept. And since NPCs would buy anything as long as they had money, players were able to earn more money more easily than the game designers had anticipated, thanks to human ingenuity and automation. To prevent this overproduction, the game designers interfered by limiting the number of items an NPC would buy per hour. Of course, this had some unintended consequences, one of which is described in Simpson’s 1999 research paper: “In order to facilitate these shopkeeper changes, the AI which required the shopkeepers to keep a positive cash flow had to be abandoned. Shopkeepers now effectively print gold in order to pay for the useless goods which are being created by the manufacturers.” Sounds familiar?

As history shows and this example illustrates, planning an economy—virtual or not—is an impossible task. Every interference, no matter how benign the central planners believe it to be, will have unintended consequences and side effects that will beget more interference. If the rules that are supposed to prevent unauthorized copying can be broken they will be broken, whether it is by the players or the gods that control the worlds they inhabit. As we will see over and over again, if the rules are untethered from the physical world, exploits will be found, rules will be changed, and economies will suffer.

Ultima Online is no exception, as Simpson points out: “In the early stages of UO, players discovered an obscure server fault which allowed them to clone certain kinds of items, primarily gold and reagents. Although the programmers discovered this cheat quickly, it took them a long time to fix it. In the interim, the existing UO worlds became saturated with gold. Estimates of the inflation value range from multiples of hundreds of thousands to millions. The hyperinflation destroyed the gold economy and players resorted to bartering and just plain-old charity during this period.”

The same story plays out over and over again, no matter if the worlds are virtual or not. If someone finds a way to create more money cheaply, they inevitably will exploit this advantage, no matter the long-term consequences. As we shall see, this is also true if the money emerges naturally in the first place.

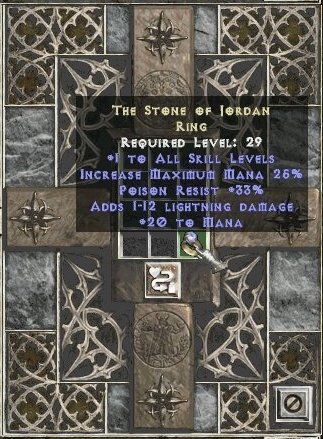

Diablo 2: Duplicating the Stone of Jordan

To me, Diablo 2 is one of the great iconic games of PC game history. Released in the summer of 2000 it quickly became one of the fastest-selling games to date, selling over a million copies in the first two weeks. I purchased my copy on the day the game launched (June 29th) and ended up playing it for thousands of hours. Alone, with friends, at LAN parties, and online. Oh, the good old times.

Similar to Ultima Online before it, Diablo 2 is an RPG. You can play in groups (parties) with other players, slay monsters, hunt for loot, and trade items with others. While Diablo 2 has an in-game currency in the form of gold, gold isn’t used to facilitate trade. The reason is that the gold that players will find in the game is horrible money. First of all, the amount of gold a player can possess is capped. Your character can only carry 10,000 gold per level, and your stash (basically your treasure chest) can only hold between 50,000 and 2,500,000 gold, also depending on your level. Second of all, every time you die a certain percentage of your gold will disappear. This death penalty will cost you up to 20% of your gold, no matter where you store it. It simply vanishes, removing itself from circulation. And third of all, gold isn’t particularly scarce. You will find it everywhere, and every NPC vendor will gladly buy whatever junk you have and give you gold for it.

All these peculiar properties make Diablo’s in-game gold horrible money. Consequently, a natural, de-facto money emerged: the Stone of Jordan.

The Stone of Jordan, or SoJ for short, was one of the unique9 (read: very rare) rings in the game. While it had desirable properties in and of itself, most players didn’t use it as an item to be equipped, but as a currency to facilitate trade. The SoJ was small and rare, which made it portable and valuable.10 Using up only one slot in a player’s inventory, many players had dozens of SoJs in their stash to be used for trading. Prices emerged naturally.11 Most desirable weapons—which usually belonged to the unique or set class—traded for single-digit amounts of SoJs. A ‘Doombringer’ sword was worth between two and four SoJs, an ‘Eaglehorn’ bow between five and seven, and a mallet known as Schaefer’s Hammer was worth between four and six SoJs. Any item that was worth less than a single SoJ was traded for one or more ‘perfect skulls,’ another de-facto currency that emerged naturally. In essence, the perfect skull was the $1 bill of the game, and the SoJ was the $5 bill of the game. Naturally, one SoJ would trade for 5 perfect skulls. Only the best items were priced in the double digits in terms of SoJs. One example would be the ‘Windforce’ bow that, coincidentally, my ‘Bowazon’ was lucky enough to hold in her hands. It was traded for around 40 SoJs.

The Stone of Jordan eventually lost its role as the de-facto money in Diablo 2. As with all obsolete money, its eventual downfall was that people found a way to make more of it, cheaply.

Inflation began gradually. Since the Stone of Jordan was such a valuable item, players began to “farm” it as best as they could. They found all kinds of ingenious ways to make it “drop” more often, inflating the supply over time.12 The game developers even introduced features into the game that would incentivize players to get rid of the additional SoJ supply. For example: if enough players sold their SoJ rings to NPC vendors, a special monster would spawn, known as the Uber Diablo—a clone of the final boss of the game.

Of course, the cheapest way to make more of something is not to farm it, but to copy it. And that’s exactly what players figured out to do. People found ways to exploit certain bugs in the game and its servers, allowing them to duplicate any item of their choosing. These dupes, as they came to be known, were perfect copies of the original item. In essence, players found a way to double-spend their digital items, leaving the game’s servers and other players none the wiser.

It didn’t take long for the in-game economy to collapse. As one player recounts: “On June 30, 2003, several key developers left Blizzard North to form new companies. By now the SoJ economy was in ruins [...]. I remember well the day when it all collapsed, prices had been inflating ever so slightly for several weeks and when I logged on that morning to do business as usual the trade channel was in a state of chaos. Stormshields were going for 20 SoJ, other higher value items were impossible to obtain. The heydays were over and everyone knew it. The once busy trade channels would slowly fade to silence...”

Eventually, the game developers were able to get a handle on the situation. Most of the bugs that allowed for this duplication to happen were fixed, and systems were put in place to identify dupes and destroy them. Of course, this destructive process wreaked even more havoc on the whole economy, at least in the short term. Many players didn’t know if their items were dupes or not, so imagine waking up one day to see that half of your possessions simply vanished overnight.

Over time, other forms of money emerged. The expansion pack “Lord of Destruction” introduced rune words into the game, and with the duping brought somewhat under control, the runes that were the atomic components of these words eventually became the new de-facto money. They share all the monetary properties that the SoJ had, and additionally, they varied in rarity. This led to runes effectively becoming the $1, $5, $10, $20, and $50 notes of the game.

With the release of Diablo 3 in 2012, the legend of the Stone of Jordan lived on. As a nod to its monetary use in the previous incarnation of the game series, the developers added the following sentence to the lore surrounding the ring: “The Stone of Jordan is far more valuable than its appearance would suggest. Men have given much to possess it.”

Once people home in on one form of money, they do indeed go through great pains to gather more of the precious good. What’s true for gold and diamonds in meatspace is also true for Stones of Jordan and other rare items in cyberspace. As we shall see, this is also true for artificially scarce goods such as designer clothes and other luxury items.

Second Life: Linden Lab’s Interventionism

Launched in 2003, the virtual world of Second Life quickly became an economic phenomenon. Second Life differs from the games mentioned previously since it isn’t necessarily a game in the first place. You don’t hunt monsters and go on quests, you are simply a resident of a virtual world. It is an alternative place to meet and do things, a world where you can be anything and anyone you want to be. In other words: it is an opportunity to start a second life.

Residents of Second Life craft all kinds of virtual goods: clothing, vehicles, houses, sculptures, gadgets, artwork—anything that can be modeled in 3D. Residents can buy cosmetics to improve the appearance of their avatars, just like we do in the real world. Skin, hair, jewelry, custom animations—if you can imagine it, someone will craft it and sell it to you. Apart from objects, some focus on providing services for their fellow residents: entertainment, education, consulting, business management, news, and yes, even banking.

As a consequence, many people ditched their real-life job to focus fully on their Second Life job. While the goods might be virtual, the profits are not, and it didn’t take long for the first self-made millionaires of Second Life to emerge. In 2006, Anshe Chung (known as Ailin Graef in her first life) became the first person to make over one million US dollars in Second Life. It took her two and a half years to build her fortune, mainly working in the virtual real estate business.

In 2009, the total size of the Second Life economy grew to USD 567 million, with gross resident earnings of USD 55 million. As of this writing,13 Second Life has about 50,000 residents logged into the virtual world at any given time, and an annual GDP of approximately USD 500 million.14 To quote Matthew Beller: “Second Life’s economy could reasonably be compared to that of a small foreign country dependent on tourism.”7

In the game itself, however, it is not US dollars that are circulating. The currency in Second Life is the Linden dollar (L$), named after Linden Lab, the company that created Second Life. Residents can acquire Linden dollars by parting with their real dollars on an exchange provided by Linden Lab.

Even though the exchange rate between the Linden dollar and the US dollar isn’t fixed, the “God” in this economy is still Linden Lab. The company controls all aspects of the game from monetary policy to physics to what is allowed in what region and who gets to be a resident and who will be banned. In short: Linden Lab has the power to break the rules and interfere as they see fit. And interfere they did, many times.

Most of these “Acts of Linden,” as they became known in the community, were initiated by the company to steer the virtual world in a certain direction or improve the bottom line of Linden Lab. One such example would be the introduction of a value-added tax for all European residents—a tax for purchasing virtual goods, mind you. Others, such as the global ban on gambling, were initiated because of pressure due to real-world government regulations. To quote the announcement of this new policy: “Second Life Residents must comply with state and federal laws applicable to regulated online gambling, even when both operators and players of the games reside outside of the US.”15

As with all complex systems, interference will often cause a whole set of intricate problems down the line. The ban on gambling, for example, led to a run on the banks by both players and operators of casinos, sports betting institutions, and other gambling businesses. Consequently, one of the largest banks in the game—Ginko Financial—collapsed, since most ATMs located in the gambling districts were owned by this bank. Residents quickly drained the reserves of the bank since Ginko Financial operated on a fractional reserve, just like banks in the real world do. The virtual bank invested its money primarily in illiquid goods or virtual securities, just like banks in the real world do. It was later described as a Ponzi scheme, just like ... you get the idea.

Consequently, another “Act of Linden” followed. Linden Lab updated their terms of services and various policies16 to include a new rule for all residents of their virtual world: everyone who offers an interest-paying service in Second Life must have a real-life banking license. The reason? Legal risks.

The following is a direct quote from the Second Life Blog: “As of January 22, 2008, it will be prohibited to offer interest or any direct return on an investment (whether in L$ or other currency) from any object, such as an ATM, located in Second Life, without proof of an applicable government registration statement or financial institution charter. We’re implementing this policy after reviewing Resident complaints, banking activities, and the law, and we’re doing it to protect our Residents and the integrity of our economy.”17

Second Life shows two things very clearly: (1) Artificially regulating a complex system is not only difficult, but it will almost always have unintended consequences that might make the problem worse. (2) If you are a centralized and identifiable entity that has the power to change the rules, the real-world state will intervene.

There is a lot to be learned from the controlled laboratory experiment that is Second Life. In many ways, Linden Labs failed to create a stable and controlled closed-loop economy, even with the godlike powers they have over all aspects of the game. As Joseph Potts put it: “whether in real life or the virtual one, the creation of money by fiat produces booms and busts, and this even in a world in which the ‘government’ can and does create (all) value.”18

Gaming and Virtual Currencies Today

Online games and the in-game economies they create are here to stay. For those who grew up with computer games, spending money on in-game goods is as normal as paying for other digital goods and services such as songs, movies, or ebooks. People will continue to spend ridiculous amounts of money on cosmetics and status symbols. Whether these goods exist in “real life” or in virtual worlds does not seem to matter. Luxurious cars, expensive watches, jewelry, designer clothes—virtual or not, the money people spend on them is real.

As of today, the most well-known game that monetizes on the purchase of cosmetic luxuries is probably Fortnite. Released in 2017, the free-to-play game has attracted more than 100 million players and earns hundreds of millions of dollars per month, mostly by selling in-game items such as skins, characters, emotes, and so on. Again: these items are pure cosmetics; they don’t improve your character or gameplay in any way, except for visuals. Some of the rarer skins sell for hundreds and sometimes even thousands of dollars. They are virtual collectibles for a digital generation.

The most recent incarnation of Counter-Strike, Counter-Strike: Global Offensive, is another game that sells expensive cosmetics. Being one of the most popular first-person shooters in the world, the only parts of your character that you see on the regular are your hands and the weapon that is held by them. Naturally, cosmetics in CS:GO are applied to what you see: weapons. While most of these weapon skins are almost worthless, some of the rare ones regularly trade hands for thousands of dollars on secondary markets. Some skins are bound to championships and thus have a unique character, such as the Dragon Lore from the Boston 2018 Major, which sold for over USD 61,000 in January 2018.19 Some collectors seem to have paid even more to purchase a single skin, with reports citing up to twice that amount (over USD 100,000).20

All of this goes to show that if left to their own devices, players will spawn vast economies as long as the game mechanics allow for it. One of the best examples of a flourishing economy (thanks to little intervention) is Eve Online, an MMORPG space simulation. The game was home to what is probably the most expensive battle in gaming history: the Bloodbath of B-R5RB, named after the star system where the battle took place.21 Players can visit 7,800 star systems in this virtual world to explore, mine, trade, and—of course—combat other players. This particular battle took place in January 2014. The tally of the losses of all involved was in the realm of 11 trillion Interstellar Kredit (ISK) or USD 330,000 at the time. I can only echo the words of Marcus Carter, Kelly Bergstrom, and Darryl Woodford: “Internet Spaceships Are Serious Business.”22

No discussion about in-game money is complete without mentioning the king of gold farming, at least in terms of real-world repercussions: World of Warcraft. The virtual gold rush and the gold farms it spawned are something to behold.23 While the gold was virtual, the (mostly criminal) organizations launched to systematically harvest the in-game currency were anything but. The idea was simple: hire a bunch of people, pay them to play for up to 20 hours a day, and sell the gold they find in the game to other players. For real money, of course. Some took the execution of this idea to the extreme. “Companies” retro-fitted warehouses to cram as many PCs and “employees” in them as possible. The only job of these employees was to play the game and farm gold. In even more extreme cases prison inmates were forced to farm the digital asset all night long.24 As Paul Tassi wrote in Forbes in 2011: “It’s been discovered that in an unknown number of Chinese prisons across the country, inmates have been forced not only to do physical labor, but electronic work as well, acting as World of Warcraft gold farmers by night.”25

It turns out that prison bosses made more money with forced in-game labor than they made with good old-fashioned forced physical labor in the real world. Prisoners were compelled to work 12-hour shifts inside the game, earning up to USD 900 per day for the prison bosses. The China Farmer phenomenon, as it came to be known in the World of Warcraft community, was not only an ethical problem, but an economic one as well. Farming is just one method to produce more of something cheaply, and if that something is money, the effects that come with inflation will burden the economy; in-game or not.

While in-game economies can have repercussions in the real world, the reverse is also true: economic events in the real world can have rippling effects that disturb virtual worlds. One such example is the hyperinflation in Venezuela, which led many people to start farming gold and other valuable in-game items to make ends meet. Venezuelans that had a computer and internet access were driven to abandon their real-world jobs, since farming and selling virtual goods to players worldwide—sometimes using bitcoin as the intermediate medium of exchange—brought in more money than they could earn regularly. As The Economist quipped: “The law of supply and demand is ignored in Venezuela, but not online.”26

So many Venezuelans farmed and traded virtual goods that when the power went out during the 2019 Venezuelan blackouts, virtual worlds such as RuneScape suffered their own economic crisis. Imagine a lively marketplace, and suddenly, one day, the vast majority of traders (and thus goods) can’t show up. After all, there is no online trading when you’re forced to be offline because the power is out.

All these examples show that games are microcosms when it comes to economies and the creation and control of money. The difference between the Linden Dollar, World of Warcraft Gold, Fortnite V-Bucks, the Euro, and the U.S. dollar is in scale, not in nature. While V-Bucks are created and controlled by Epic Games (the company that created Fortnite), the U.S. dollar is created and controlled by the Fed. One impacts millions of people, the other billions. The mechanism that keeps these monies in check—the rules of the game, if you will—is the same in both cases: central decree.

While the worlds are virtual, the time and effort that people are willing to put into building and equipping their avatars are not. Consequently, real economies can emerge in virtual worlds. However, as we have seen, these virtual economies are neither long-term persistent nor independent of their virtual arenas.

Herein lies the crux of virtual currencies: they are created, managed, and kept alive by central decree. They only exist in their respective arenas—in-game or otherwise. Consequently, they do not transcend boundaries. It is impossible to spend your in-game money outside of the game, just like it is impossible to spend your bolívars or lira outside of your failing country.

However, even when trapped inside the borders of these walled gardens, people will find ways to trade their virtual goods on real marketplaces, no matter if they are allowed to do so or not. As soon as this happens, the authorities usually step in. The companies who instantiate the virtual worlds will intervene out of self-interest or because a government forces them to, as was the case with Second Life. In most cases, the companies want to have a piece of the pie: a cut for every transaction that happens inside their world. Ironically, this is also one of the reasons for government intervention: they want their “fair share” too.

It is simple, really: if a world is controlled and instantiated by a single entity, it is prone to manipulation. Sooner or later, it will cease to exist. And with it, everything that existed inside it.

What we need is a non-virtual world, a persistent world. A world that refuses to disappear.

Emergent Money in a Non-Virtual World

Bitcoin is different in two ways: First of all, bitcoin’s value does not come from central decree. Like gold before it, its scarcity and persistence do not derive from authority, but from reality. Gold is scarce because physical laws make its creation and production extraordinarily costly. Gold doesn’t go away because it is virtually indestructible.

Bitcoin brings digital objects into existence—sats—that are bound to the digital world of the bitcoin network. How is this any different from the various in-game monies that emerged before it?

It is different because both the environment as well as its monetary units emerge naturally over time. Bitcoin is not instantiated by decree; neither are sats brought into existence by decree. Bitcoin’s monetary units, their value, and Bitcoin’s arena emerge naturally over time, via voluntary interaction of anyone who is willing to participate.

The difference lies in the nature of the arena, as well as in the issuance and control of the monetary units, which, when centrally controlled, are the source and root of all monetary evil, as Hayek said so poignantly.

[Free trade in money] seems to me both preferable and more practicable than the utopian scheme of introducing a new European currency, which would ultimately only have the effect of more deeply entrenching the source and root of all monetary evil, the government monopoly of the issue and control of money.

F. A. Hayek

The problem of issuance relates to the monetary units themselves: who can make more of them? The problem of control relates to the environment that said monetary units inhabit: who can change the rules?

In very general terms, this problem is always the same. There are objects, and there is the environment that allows these things to exist: the respective arena. In the physical world, we call the relationship between objects physical laws—because they can’t be broken—and we call the arena the universe. We also have objects and arenas in the world of gaming: items that make players more powerful, and the virtual worlds they inhabit. While most in-game monies, such as the Linden Dollar, are brought about by decree, some in-game monies emerge naturally, as evidenced by the monetary use of the Stone of Jordan in Diablo II.

When it comes to fiat money, the arena is the nation-state. The objects used to be physical: coins and paper notes. Today, they are mostly virtual: zeroes and ones in a central bank server. In any case, fiat money is untethered from economic reality. It is a made-up construct, which is why all fiat monies go away over time. Either the money collapses due to hyperinflation, or the arena collapses due to the end of the nation.

Whether we look at computer games or fiat money, the questions we have to ask when it comes to money are the same: Who can create more of it? Is there a way to farm it effectively? And, most importantly: Who is in charge of the arena?

History shows that any rules that can be broken will be broken. Consequently, we can assert the following with confidence: If the objects are virtual—disconnected from reality—they can be created at a whim. If there is a mechanism to make more of a desired good—virtual or not—some ingenious humans will find a way to do so efficiently.27 If the arena is virtual—if the environment is disconnected from reality—the rules of the game can be changed arbitrarily, and, even more catastrophically, the arena can disappear.

When it comes to in-game currencies, the company that is running the game servers might go bankrupt or decides to shut down operations for other reasons. When it comes to fiat currencies, the nation-state that forces you to use its fiat money might go bankrupt or ceases to exist for other reasons.

As a shorthand, we might call the aforementioned questions print-farm-serve, short for: Can it be printed? Can it be farmed? Is it served? If the answer to any of these questions is yes, then you are most definitely dealing with bad money.

When looking at the trifecta of print-farm-serve through the lens of Bitcoin, most people will know by now that only 21 million will ever exist, i.e. that you can’t print more of it. Fewer people will understand the difficulty adjustment, which is the mechanism that allows Bitcoin’s monetary issuance to be fixed in time, i.e. the mechanism that makes the efficient farming of bitcoin impossible. Only very few will understand the last part: the fact that Bitcoin isn’t served, that it arises out of your personal view, and the overlap of this view with others. Most skeptics still believe that Bitcoin will go away just like all the virtual worlds that came before it.

The skeptics are right to be skeptical. Ephemerality is one trait that all virtual worlds share, along with the virtual monies that exist in them: they all go away, eventually. After all, they are virtual, not real. They are simulations: made-up constructs, a cheap imitation of reality.

How is Bitcoin different?

Digital Reality

Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.

Philip K. Dick

While the world of Bitcoin is a digital world, it is not a virtual world. It is not a made-up world. Yes, the rules were “made up” by Satoshi—but they are neither arbitrary nor can they be changed arbitrarily. More importantly, the world that arises out of these rules is not virtual. It is not a simulated world. It requires real cost, real time, real energy—and, consequently—real sacrifice to maintain itself. It is not a world by decree; it is a non-virtual world that arises out of the manipulation of bits and bytes. A shared view of past events, rooted in the physical and mathematical laws of our universe.

Bitcoin is not a simulation. Consequently, the digital scarcity of bitcoin is not virtual. It arises out of real, physical limits. The rules of Bitcoin’s difficulty adjustment do not simulate physical laws, they are brought into existence because of physical laws.

Bitcoin consists of numbers. For this reason, it might be tempting to discuss the metaphysical question of whether numbers are real or not, and plenty of philosophical ink was spilled in attempts to answer this question. I will refrain from trying to answer the question of what ultimately constitutes reality. Is it particles? Strings? Fields? Information? Interaction? Connection? Value?

Whatever reality is, Bitcoin maps onto it.

Bitcoin does not care about the answers to these metaphysical questions. It is a pragmatic solution that does not care whether numbers are real or not. A practical solution that works independently of metaphysical speculations of reality. Bitcoin’s realness does not arise out of the realness of numbers, but out of the realness of computation, which is to say out of the realness of energy. There is no way to do computation without expending energy. The physical laws of our universe forbid it. It is this limitation that is at the root of all cryptography.

Cryptography is the exploitation of this law via the application of mathematical extremes. At the extremes, the mathematical becomes physical. In theory, you could guess Satoshi’s private key. And yet it is virtually impossible in practice. In theory, you could mine a hundred valid bitcoin blocks in five seconds. Yet, again, it is virtually impossible in practice.

Bitcoin is not a simulation because certain bits can only be brought about by expensive physical processes. These processes can not be simulated, because they are rooted in computation itself. There is no shortcut to these computations, which is why the physics inherent in computation—the very physical process of flipping bits—is undeniably embedded in the information that is produced.

The randomness of proof-of-work is a feature, not a bug. There is no progress towards a solution. There are no shortcuts and there can’t be any shortcuts. Randomness is what makes it fair and resistant to cheating. Remove this randomness, and you are back at something that is given by decree. Remove the difficulty adjustment, and you are back at something that can be farmed.

The only way to produce a valid proof-of-work is to actually do the work. This is what makes Bitcoin real; this is what transfers the physical limits of our universe into the digital world of Bitcoin. This is what makes Bitcoin more than a fancy telephone. Bitcoin doesn’t only connect people, but it uses proof-of-work to connect itself to the physical world.

Proof-of-work can’t be argued with. The information that is brought into existence via proof-of-work can only exist because certain things happened in the real world. Certain events that are so improbable, so incredibly unlikely, that they had to happen in actuality, even though every single event was a digital event.

Proof-of-work has the nice property that it can be relayed through untrusted middlemen. We don’t have to worry about a chain of custody of communication. It doesn’t matter who tells you a [heaviest] chain, the proof-of-work speaks for itself.

Satoshi Nakamoto

Bitcoin’s difficulty-adjusted proof-of-work is what makes Bitcoin a real phenomenon, something to be wrestled with. It is what makes it non-virtual, non-imaginary.

The numbers that make a valid block valid are too improbable to be dreamt up by anyone. They can only exist because real people invested real time and real energy—using real machinery—to bring them about. The numbers might be random, but the process that brings them about is not. The parameters might be arbitrary, but the digital universe they create is not.

Emergent Money in an Emergent World

One question remains: why won’t Bitcoin die? Why doesn’t it go away? To answer this, we have to talk about two other aspects of the proof-of-work coin: validation and instantiation.

If you are the inhabitant of someone else’s world—if the arena is “served”—you will always be at your master’s mercy. You will always be bound to their rules. That is true in computer games and nation-states alike. The game changes if you can “run your own,” which is what makes you independent of any masters. If you run your own instance—if you create your own world—you won’t have to bow down to anyone else. You just have to subjugate yourself to the laws of nature.

In Bitcoin, anyone can create both the objects and the arena. Anyone can mine. Anyone can run a node.

A node is what builds up and verifies the digital world of Bitcoin, from the very beginning, including all rules and all past states. The world of Bitcoin arises out of the overlap of all these individual worlds. It is not a shared world, it is a world of consensus that arises out of agreement. Agreement about what happened in the past and what should happen in the future. Agreement via independent repetition of the same experiment and arriving at the same conclusion.

A “miner” is what extends the digital world of Bitcoin. Miners are in the business of block production, which is to say in the business of proposing a new block of past events to the network. If the events are in accordance with the rules, nodes will accept them. If they are not, nodes will reject them. Miners extend the arena, and in doing so, are rewarded with sats—the most precious objects in the world of Bitcoin. Anyone can participate in block production. All that is required is an energy source and a communications channel.

Herein lies the main difference when compared to fiat and in-game money: you don’t have to rely on anyone to bring Bitcoin about. You can do it all yourself.

Bitcoin is here to stay because it is cheap and easy to bring into existence. It is a networked phenomenon that emerges out of equal peers, not unlike electricity and the internet before it. The fear of Bitcoin ceasing to exist arises out of a deep misunderstanding of the nature of these phenomena. It is akin to asking: “What if electricity goes away?”

Electricity isn’t a magical thing given to us by the high priests of the Ministry of Electrons. Take a magnet, take a copper wire, and voilà! You have electricity. Anyone can generate electricity at all times, as long as they are doing the required work. Electricity is here to stay precisely because it is not brought about by authority. It is a natural phenomenon, brought about by physical interaction. There is no central authority in charge of making it.

Networked computing won’t go away either, and for the same reason. Take two computers, plug them together, and voilà! You have a network. Plug many networks together, and voilà! You have the internet. The thing about the internet is that it’s most useful when it’s largest, which is why we have one internet, not many.28

The same goes for Bitcoin: run free and open-source software on your computer, connect it to another node with compatible consensus rules, and voilà! You have Bitcoin.

By running consensus software you decide which rules are important to you. In other words: you decide what Bitcoin is, and it is you who brings it about—both philosophically, and technically. There are no servers. You create your own world. And if you’re lucky, your view of the world will overlap sufficiently so that you can communicate and trade with others. You are free to extend this world, both in accordance with the rules (block production) and by introducing new rules (forks). If your rule change is incompatible, your world will cease to overlap with the worlds of others, leaving you stranded on an island of one.29

Unlike most virtual worlds, the world of Bitcoin arises out of the intersection of individual points of view. It is not served by authority but emerges organically out of the agreement of equal peers. The extension of this digital world is physical and costly. Verification is mathematical and cheap. It is this asymmetry that brings about the game theory that keeps everything in balance.

As long as someone cares about fair, censorship-resistant money that is independent of the state, Bitcoin will exist. Even if that someone is only one person. Even if that someone is just you.

Conclusion

Before Bitcoin, all digital money was virtual money. Most virtual monies are fiat monies, only money because some authority says so. Even when money emerged naturally in networked games, the worlds that form these arenas were always virtual worlds. Designed, controlled, and maintained by central authorities. Authorities with the power to change the rules, something that they will always do, either out of self-interest or emergency. As we have seen, if a central authority can be identified, the state will step in and force a rule change.

The difference between in-game money and fiat money is in scale, not in nature. Both are virtual: simulations that are untethered from reality. And with the introduction of CBDCs, both will be completely digital as well.

Bitcoin is the first money that is digital but not virtual. Before Bitcoin, any link between the digital and the physical was always rooted in trust and human interpretation, not physical reality. Bitcoin’s link to the real world is defined by numbers and their mathematical relationships; relationships so extreme, that they can only be brought about by real events in the real world. Consequently, the processes in Bitcoin are not subject to opinion or interpretation. They are not a simulation, which is why Bitcoin can’t be paused, restarted, or stopped.

The metaphysical properties of Bitcoin are independent of the metaphysical nature of numbers. The fact that Bitcoin is “just numbers” is unimportant. What is important is the process that brings about these numbers, which is a process that can’t be faked, cheated, or simulated. We know, without a doubt, that the only way to bring a valid bitcoin block into existence is by expending real energy in the real world.

Jaron Lanier quipped that “information is not something that exists.” I disagree. Information that can only exist because of expensive physical processes has a certain reality to it. It is incontrovertible proof that something happened in the real world. It is “more real” than the words that you are currently reading. After all, this paragraph could’ve been cheaply generated by GPT-3. A valid bitcoin block? Not so much.

Bitcoin creates a digital world that, at first glance, might be compared to the virtual worlds of computer games. What we call “sats” can be understood as endogenous items of the Bitcoin game. As we have seen in Chapter 3, sats had no monetary value for the first 10 months. The moneyness of sats had to emerge over time, which is what makes bitcoin natural money, not fiat money. Sats have all the properties that are required of good money—which is why they are used as money, just like the Stone of Jordan was natural money in the virtual world of Diablo II, and gold was natural money in the physical world. However, unlike the Stone of Jordan, sats can be instantiated by anyone, which is what makes them persistent. And unlike gold, sats are natively digital.

When it comes to money, two questions are of utmost importance: (1) Who has the authority to create it? (2) Can the mechanism of money creation be abused?

When it comes to digital money, a third question needs to be answered: Who is in charge of the arena?

In the virtual worlds of computer games and fiat monies, whoever is running the servers is in charge. In Bitcoin, it is you and you alone who is in charge. You and the truth are the final authority, brought about by mathematics and the physical laws of our universe.

The questions surrounding printing, farming, and serving point to the reasons why digital monies failed in the past, and why CBDCs will fail in the future:

- “admins” abuse their powers and print more outright,

- “players” find ways to make more of it cheaply,

- “the arena” ceases to exist, either because of bankruptcy, intervention, or collapse.

The combination of non-simulatable proof-of-work with cheap, independent verification and instantiation is what separates Bitcoin from all the monies that came before it.

Bitcoin creates a digital arena, not a virtual one. It is defined by reality, not authority. The use of sats as money emerged naturally, not by decree. Bitcoin’s arena is instantiated by individuals who are voluntarily agreeing to a set of rules, as opposed to virtual worlds that are instantiated by rulers who dictate the rules for all.

Bitcoin is scarce because time and energy are scarce. The issuance of sats is related to time, not energy. The energy cost is dynamic and completely unrelated to issuance. More energy won’t produce more bitcoin, it will only disperse the bitcoin that would be issued anyway more widely while making the Bitcoin network more secure. As we have seen in Chapter 2, the fact that block production requires electricity is a feature, not a bug. It acts as an unforgeable costly signal that is used to build up a trustless arrow of time, as well as a transparent and publicly verifiable shield around the past. It is an anti-cheat mechanism to ensure that the past can’t be altered cheaply and to ensure that future issuance can’t be farmed efficiently.

Consequently, Bitcoin’s energy consumption is not a byproduct of the creation of sats, but a by-product of demand for a fair distribution of sats. If the demand for sats had stayed with Satoshi and Satoshi alone, Bitcoin’s energy use would be close to zero. If it would’ve stayed like this for all of Bitcoin’s bootstrapping phase, Satoshi would have had 100% of the initial coin distribution. After the bootstrapping phase, it will still be about the fair distribution of sats, but the sats will be paid, not issued. Energy use is thus related to decentralization and security, nothing else.

In short: bitcoin can’t be printed because it is automatically issued over time. The system can’t be cheated because energy can’t be copied. Proof-of-work can’t be simulated, and the difficulty adjustment forbids the “farming” of blocks. Anyone can participate in, instantiate, and validate everything.

Bitcoin is a digital item in a digital environment, brought about and kept alive by physical processes. It is the combination of the physical with the digital that gives Bitcoin its power: a digital commodity that can be sent around at the speed of light, inexorably linked to the physical laws of our universe. It is digital gold, not virtual gold.

Virtual currencies like in-game currencies and fiat currencies are not scarce, because they require neither time nor energy to create. God-like entities can create them out of thin air. This is true even if money emerges naturally in a virtual arena, as was the case in Diablo II. As long as the arena is virtual, it can be controlled and shut down. The difference between central banks and game developers is one of quantity, not quality.

Gold was sound money that emerged naturally in the physical world. It does not have the problem of a disappearing arena. Because for gold, the arena is the physical universe.

Bitcoin is sound money that emerged naturally in the digital world. And as it continues to monetize, more and more people will understand that it too does not have the problem of a disappearing arena. For bitcoin, the arena is the mathematical universe. And as long as a single copy of the timechain remains intact, Bitcoin will survive.

Gold’s physicality is its biggest downside: it is a physical item in a physical environment. Consequently, you can neither store it in your head nor send it to others at the speed of light.

Bitcoin fixes this. It is a digital commodity in a digital environment, brought about and protected by physical processes that can’t be cheated. Bitcoin’s proof-of-work reifies Bitcoin’s blocks as well as the monetary units within them, and it is this reification of information that allows Bitcoin to transcend the mere virtual.

But Bitcoin transcends more than just the virtual. It also transcends all other monies that came before it, by introducing something that cannot be improved upon further, something that did not and can not exist in the physical world: absolute limitation via zero terminal inflation.

21 million. Absolute scarcity.

Cory Doctorow (2012), The Rapture of the Nerds ↩

Marc Andreessen (2011), Why Software Is Eating the World ↩

Definition of ‘virtual’ from The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, 5th Edition. ↩

Julian Dibbell (1995), MUD Money: A Talk on Virtual Value and, Incidentally, the Value of the Virtual ↩

Massively multiplayer online role-playing game. ↩

Zachary Booth Simpson (1999), The In-game Economics of Ultima Online, Origin Research ↩

Matthew Beller (2007), The Coming Second Life Business Cycle ↩ ↩2

Non-player characters. ↩

Unique items in Diablo 2 aren’t unique in the literal sense, but belong to the “unique” class. Other classes are normal, superior, magic, rare, set, and crafted. Unique items are exceedingly rare, meaning that the odds that they will spawn more than once each game are nearly impossible. ↩

Daniel McNally (2012). It’s all Monopoly Money Now ↩

Salter, A. W., & Stein, S. (2016). Endogenous currency formation in an online environment: The case of Diablo II. The Review of Austrian Economics, 29(1), 53-66. ↩

It is worth pointing out at this point that our current fiat monies such as the USD can be farmed too. The easiest way to farm fiat is not by doing work, however, but by taking on debt. ↩

Daniel Voyager (2022). Second Life Grid Statistics ↩

Nick Galov (2022). Second Life in 2022: What It Means to Live in a Virtual World ↩

Robin Linden (2007), Wagering In Second Life: New Policy, Second Life Blog ↩

Linden Lab (2011), Official Policy Regarding In-World Banks, Second Life Wiki ↩

Ken D Linden (2008), New Policy Regarding In-World “Banks”, Second Life Blog ↩

Joseph Potts (2007), And Thus It Came to Pass, Mises Wire ↩

Andy Chalk (2018), CS:GO ‘Dragon Lore’ AWP skin sells for more than $61,000 ↩

Nikola Savic (2020), Someone paid $100,000+ for a CS:GO skin, the most expensive skin purchase in history ↩

Wikipedia, Battle of B-R5RB ↩

Marcus Carter, Kelly Bergstrom, and Darryl Woodford (2016), Internet Spaceships Are Serious Business, University of Minnesota Press ↩

Gold Farming, Wikipedia ↩

Danny Vincent (2011), China used prisoners in lucrative internet gaming work, The Guardian ↩

Paul Tassi (2011), Chinese Prisoners Forced to Farm World of Warcraft Gold, Forbes ↩

The Economist (2019), Venezuela’s paper currency is worthless, so its people seek virtual gold ↩

Diamonds are one example of a real-world good that used to be scarce but can now be farmed. Thanks to human ingenuity, diamonds can be produced artificially. To quote the U.S. National Minerals Information Center: “Synthetic industrial is superior to its natural diamond counterpart because it can be produced in unlimited quantities, and, in many cases, its properties can be tailored for specific applications. Consequently, manufactured diamond accounts for more than 90% of the industrial diamond used in the United States.” ↩

The History of the Internet clearly shows that we used to have many different networks. Today we have one, because like most networks that are open and global, the Internet is a winner-takes-all phenomenon. ↩

We will discuss soft- and hard forks in detail in Chapter 16. ↩

Translations

- German translation by Der Geier

- Spanish translation by Dr. Jones

- Spanish translation (1) by Evariste Galois

- Spanish translation (2) by Evariste Galois

- Spanish translation (3) by Evariste Galois

- Spanish translation (4) by Evariste Galois

- Spanish translation (5) by Evariste Galois

- Spanish translation (6) by Evariste Galois

- Spanish translation (7) by Evariste Galois

- Spanish translation (8) by Evariste Galois

- Italian translation by Fillippone

- English discussion by Guy Swann

- English audio by Guy Swann

- Italian translation by Italian Satoshi

- Spanish translation by La Taberna de Bitcoin

- Greek translation by Nina

- German audio by Rob

- French translation by Sovereign Monk

Want to help? Add a translation!

🧡

Found this valuable? Don't have sats to spare? Consider sharing it, translating it, or remixing it.Confused? Learn more about the V4V concept.