Money doesn’t grow on trees. To believe that it does is foolish, and our parents make sure that we know about that by repeating this saying like a mantra. We are encouraged to use money wisely, to not spend it frivolously, and to save it in good times to help us through the bad. Money, after all, does not grow on trees.

Bitcoin taught me more about money than I ever thought I would need to know. Through it, I was forced to explore the history of money, banking, various schools of economic thought, and many other things. The quest to understand Bitcoin lead me down a plethora of paths, some of which I try to explore in this series. This is the second of three parts:

In Part I of this series, some of the philosophical questions Bitcoin touches on were discussed. Part II will take a closer look at money and economics. Again, I will only be able to scratch the surface. Bitcoin is not only ambitious, but also broad and deep in scope, making it impossible to cover all relevant topics in a single essay, article, or book. I am starting to doubt if it is even possible at all.

Bitcoin is a child of many disciplines. Being a new form of money, learning about economics is paramount in understanding it. Dealing with the nature of human action and the interactions of economic agents, economics is probably one of the largest and fuzziest pieces of the Bitcoin puzzle.

Like the first part, this essay is an exploration of the various things I have learned from Bitcoin. And just like the first part, it is a personal reflection of my journey down the rabbit hole. Having no background in economics, I am definitely out of my comfort zone and aware that any understanding I might have is incomplete. Like blind monks examining an elephant, everyone who approaches this novel technology does so from a different angle and will come to different conclusions. Blindfolded as I am, I will try to outline what I have learned, even at the risk of making a fool out of myself. After all, I am still trying to answer the question:

“What have you learned from Bitcoin?”

After seven lessons examined through the lens of philosophy, let’s use the lens of economics to look at seven more. I hope that you will find the world of Bitcoin as educational, fascinating and entertaining as I did and still do. In any case, hop on and enjoy the ride. Economy class is all I can offer this time. Final destination: sound money.

Find lessons 1-7 here.

Lesson 8: Financial Ignorance

One of the most surprising things, to me, was the amount of finance, economics, and psychology required to get a grasp of what at first glance seems to be a purely technical system — a computer network. To paraphrase a little guy with hairy feet: “It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, stepping into Bitcoin. You read the whitepaper, and if you don’t keep your feet, there’s no knowing where you might be swept off to.”

To understand a new monetary system, you have to get acquainted with the old one. I began to realize very soon that the amount of financial education I enjoyed in the educational system was essentially zero.

Like a five-year-old, I began to ask myself a lot of questions: How does the banking system work? How does the stock market work? What is fiat money? What is regular money? Why is there so much debt? How much money is actually printed, and who decides that?

After a mild panic about the sheer scope of my ignorance, I found reassurance in realizing that I was in good company.

Isn’t it ironic that Bitcoin has taught me more about money than all these years I’ve spent working for financial institutions? …including starting my career at a central bank”

I’ve learned more about finance, economics, technology, cryptography, human psychology, politics, game theory, legislation, and myself in the last three months of crypto than the last three and a half years of college”

These are just two of the many confessions all over twitter. Bitcoin, as was explored in part one, is a living thing. Mises argued that economics also is a living thing. And as we all know from personal experience, living things are inherently difficult to understand.

A scientific system is but one station in an endlessly progressing search for knowledge. It is necessarily affected by the insufficiency inherent in every human effort. But to acknowledge these facts does not mean that present-day economics is backward. It merely means that economics is a living thing — and to live implies both imperfection and change.”

We all read about various financial crises in the news, wonder about how these big bailouts work and are puzzled over the fact that no one ever seems to be held accountable for damages which are in the trillions. I am still puzzled, but at least I am starting to get a glimpse of what is going on in the world of finance.

Some people even go as far as to attribute the general ignorance on these topics to systemic, willful ignorance. While history, physics, biology, math, and languages are all part of our education, the world of money and finance surprisingly is only explored superficially, if at all. I wonder if people would still be willing to accrue as much debt as they currently do if everyone would be educated in personal finance and the workings of money and debt. Then I wonder how many layers of aluminum make an effective tinfoil hat. Probably three.

Those crashes, these bailouts, are not accidents. And neither is it an accident that there is no financial education in school. […] It’s premeditated. Just as prior to the Civil War it was illegal to educate a slave, we are not allowed to learn about money in school.”

Like in The Wizard of Oz, we are told to pay no attention to the man behind the curtain. Unlike in The Wizard of Oz, we now have real wizardry: a censorship-resistant, open, borderless network of value-transfer. There is no curtain, and the magic is visible to anyone.

Bitcoin taught me to look behind the curtain and face my financial ignorance.

Lesson 9: Inflation

Trying to understand monetary inflation, and how a non-inflationary system like Bitcoin might change how we do things, was the starting point of my venture into economics. I knew that inflation was the rate at which new money was created, but I didn’t know too much beyond that.

While some economists argue that inflation is a good thing, others argue that “hard” money which can’t be inflated easily —as we had in the days of the gold standard — is essential for a healthy economy. Bitcoin, having a fixed supply of 21 million, agrees with the latter camp.

Usually, the effects of inflation are not immediately obvious. Depending on the inflation rate (as well as other factors) the time between cause and effect can be several years. Not only that, but inflation affects different groups of people more than others. As Henry Hazlitt points out in Economics in One Lesson: “The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups.”

One of my personal lightbulb moments was the realization that issuing new currency — printing more money — is a completely different economic activity than all the other economic activities. While real goods and real services produce real value for real people, printing money effectively does the opposite: it takes away value from everyone who holds the currency which is being inflated.

Mere inflation — that is, the mere issuance of more money, with the consequence of higher wages and prices — may look like the creation of more demand. But in terms of the actual production and exchange of real things it is not.”

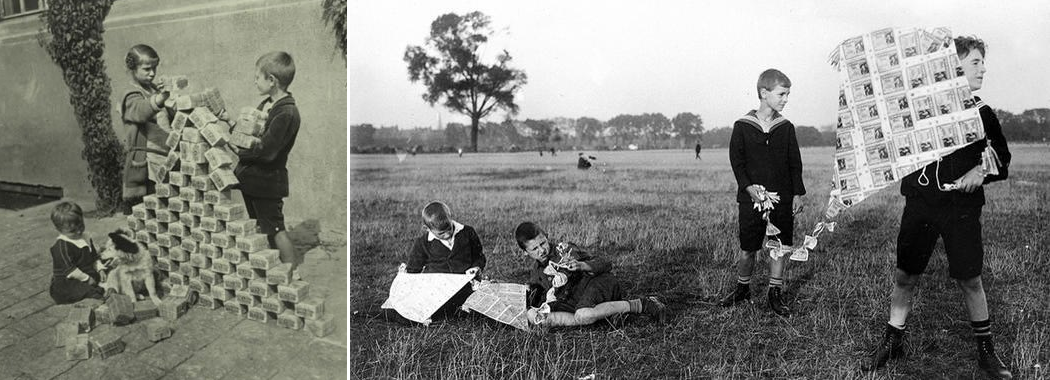

The destructive force of inflation becomes obvious as soon as a little inflation turns into a lot. If money hyperinflates, things get ugly real quick. As the inflating currency falls apart, it will fail to store value over time and people will rush to get their hands on any goods which might do.

Another consequence of hyperinflation is that all the money which people have saved over the course of their life will effectively vanish. The paper money in your wallet will still be there, of course. But it will be exactly that: worthless paper.

Money declines in value with so-called “mild” inflation as well. It just happens slowly enough that most people don’t notice the diminishing of their purchasing power. And once the printing presses are running, currency can be easily inflated, and what used to be mild inflation might turn into a strong cup of inflation by the push of a button. As Friedrich Hayek pointed out in one of his essays, mild inflation usually leads to outright inflation.

“Mild” steady inflation cannot help — it can lead only to outright inflation.”

Inflation is particularly devious since it favors those who are closer to the printing presses. It takes time for the newly created money to circulate and prices to adjust, so if you are able to get your hands on more money before everyone else’s devaluates you are ahead of the inflationary curve. This is also why inflation can be seen as a hidden tax because in the end governments profit from it while everyone else ends up paying the price.

I do not think it is an exaggeration to say history is largely a history of inflation, and usually of inflations engineered by governments for the gain of governments.”

So far, all government-controlled currencies have eventually been replaced or have collapsed completely. No matter how small the rate of inflation, “steady” growth is just another way of saying exponential growth. In nature as in economics, all systems which grow exponentially will eventually have to level off or suffer from catastrophic collapse.

“It can’t happen in my country,” is what you’re probably thinking. You don’t think that if you are from Venezuela, which is currently suffering from hyperinflation. With an inflation rate of over 1 million percent, money is basically worthless.

It might not happen in the next couple of years, or to the particular currency used in your country. But a glance at the list of historical currencies shows that it will inevitably happen over a long enough period of time. I remember and used plenty of those listed: the Austrian schilling, the German mark, the Italian lira, the French franc, the Irish pound, the Croatian dinar, etc. My grandma even used the Austro-Hungarian Krone. As time moves on, the currencies currently in use will slowly but surely move to their respective graveyards. They will hyperinflate or be replaced. They will soon be historical currencies. We will make them obsolete.

History has shown that governments will inevitably succumb to the temptation of inflating the money supply.”

Why is Bitcoin different? In contrast to currencies mandated by the government, monetary goods which are not regulated by governments, but by the laws of physics, tend to survive and even hold their respective value over time. The best example of this so far is gold, which, as the aptly-named Gold-to-Decent-Suit Ratio shows, is holding its value over hundreds and even thousands of years. It might not be perfectly “stable” — a questionable concept in the first place — but the value it holds will at least be in the same order of magnitude.

If a monetary good or currency holds its value well over time and space, it is considered to be hard. If it can’t hold its value, because it easily deteriorates or inflates, it is considered a soft currency. The concept of hardness is essential to understand Bitcoin and is worthy of a more thorough examination. We will return to it in the last economic lesson: sound money.

As more and more countries suffer from hyperinflation, more and more people will have to face the reality of hard and soft money. If we are lucky, maybe even some central bankers will be forced to re-evaluate their monetary policies. Whatever might happen, the insights I have gained thanks to Bitcoin will probably be invaluable, no matter the outcome.

Bitcoin taught me about the hidden tax of inflation and the catastrophe of hyperinflation.

Lesson 10: Value

Value is somewhat paradoxical, and there are multiple theories which try to explain why we value certain things over other things. People have been aware of this paradox for thousands of years. As Plato wrote in his dialogue with Euthydemus, we value some things because they are rare, and not merely based on their necessity for our survival.

And if you are prudent you will give this same counsel to your pupils also — that they are never to converse with anybody except you and each other. For it is the rare, Euthydemus, that is precious, while water is cheapest, though best, as Pindar said.”

This paradox of value shows something interesting about us humans: we seem to value things on a subjective basis, but do so with certain non-arbitrary criteria. Something might be precious to us for a variety of reasons, but things we value do share certain characteristics. If we can copy something very easily, or if it is naturally abundant, we do not value it.

It seems that we value something because it is scarce (gold, diamonds, time), difficult or labor-intensive to produce, can’t be replaced (an old photograph of a loved one), is useful in a way in which it enables us to do things which we otherwise couldn’t, or a combination of those, such as great works of art.

Bitcoin is all of the above: it is extremely rare (21 million), increasingly hard to produce (reward halvening), can’t be replaced (a lost private key is lost forever), and enables us to do some quite useful things. It is arguably the best tool for value transfer across borders, virtually resistant to censorship and confiscation in the process, plus, it is a self-sovereign store of value, allowing individuals to store their wealth independent of banks and governments, just to name two.

Bitcoin taught me that value is subjective but not arbitrary.

Lesson 11: Money

What is money? We use it every day, yet this question is surprisingly difficult to answer. We are dependent on it in ways big and small, and if we have too little of it our lives become very difficult. Yet, we seldom think about the thing which supposedly makes the world go round. Bitcoin forced me to answer this question over and over again: What the hell is money?

In our “modern” world, most people will probably think of pieces of paper when they talk about money, even though most of our money is just a number in a bank account. We are already using zeros and ones as our money, so how is Bitcoin different? Bitcoin is different because at its core it is a very different type of money than the money we currently use. To understand this, we will have to take a closer look at what money is, how it came to be, and why gold and silver was used for most of commercial history.

In this sense, it’s more typical of a precious metal. Instead of the supply changing to keep the value the same, the supply is predetermined and the value changes.”

Seashells, gold, silver, paper, bitcoin. In the end, money is whatever people use as money, no matter its shape and form, or lack thereof.

Money, as an invention, is ingenious. A world without money is insanely complicated: How many fish will buy me new shoes? How many cows will buy me a house? What if I don’t need anything right now but I need to get rid of my soon-to-be rotten apples? You don’t need a lot of imagination to realize that a barter economy is maddeningly inefficient.

The great thing about money is that it can be exchanged for anything else — that’s quite the invention! As Nick Szabo brilliantly summarizes in Shelling Out: The Origins of Money, we humans have used all kinds of things as money: beads made of rare materials like ivory, shells, or special bones, various kinds of jewelry, and later on rare metals like silver and gold.

Being the lazy creatures we are, we don’t think too much about things which just work. Money, for most of us, works just fine. Like with our cars or our computers, most of us are only forced to think about the inner workings of these things if they break down. People who saw their life-savings vanish because of hyperinflation know the value of hard money, just like people who saw their friends and family vanish because of the atrocities of Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia know the value of privacy.

The thing about money is that it is all-encompassing. Money is half of every transaction, which imbues the ones who are in charge with creating money with enormous power.

Given that money is one half of every commercial transaction and that whole civilizations literally rise and fall based on the quality of their money, we are talking about an awesome power, one that flies under the cover of night. It is the power to weave illusions that appear real as long as they last. That is the very core of the Fed’s power.”

Bitcoin peacefully removes this power, since it does away with money creation and it does so without the use of force.

Money went through multiple iterations. Most iterations were good. They improved our money in one way or another. Very recently, however, the inner workings of our money got corrupted. Today, almost all of our money is simply created out of thin air by the powers that be. To understand how this came to be I had to learn about the history and subsequent downfall of money.

If it will take a series of catastrophes or simply a monumental educational effort to correct this corruption remains to be seen. I pray to the gods of sound money that it will be the latter.

Bitcoin taught me what money is.

Lesson 12: The history and downfall of money

Many people think that money is backed by gold, which is locked away in big vaults, protected by thick walls. This ceased to be true many decades ago. I am not sure what I thought, since I was in much deeper trouble, having virtually no understanding of gold, paper money, or why it would need to be backed by something in the first place.

One part of learning about Bitcoin is learning about fiat money: what it means, how it came to be, and why it might not be the best idea we ever had. So, what exactly is fiat money? And how did we end up using it?

If something is imposed by fiat, it simply means that it is imposed by formal authorization or proposition. Thus, fiat money is money simply because someone says that it is money. Since all governments use fiat currency today, this someone is your government. Unfortunately, you are not free to disagree with this value proposition. You will quickly feel that this proposition is everything but non-violent. If you refuse to use this paper currency to do business and pay taxes the only people you will be able to discuss economics with will be your cellmates.

The value of fiat money does not stem from its inherent properties. How good a certain type of fiat money is, is only correlated to the political and fiscal (in)stability of those who dream it into existence. Its value is imposed by decree, arbitrarily.

Until recently, two types of money were used: commodity money, made out of precious things, and representative money, which simply represents the precious thing, mostly in writing.

We already touched on commodity money above. People used special bones, seashells, and precious metals as money. Later on, mainly coins made out of precious metals like gold and silver were used as money. The oldest coin found so far is made of a natural gold-and-silver mix and was made more than 2700 years ago. If something is new in Bitcoin, the concept of a coin is not it.

Turns out that hoarding coins, or hodling, to use today’s parlance, is almost as old as coins. The earliest coin hodler was someone who put almost a hundred of these coins in a pot and buried it in the foundations of a temple, only to be found 2500 years later. Pretty good cold storage if you ask me.

One of the downsides of using precious metal coins is that they can be clipped, effectively debasing the value of the coin. New coins can be minted from the clippings, inflating the money supply over time, devaluing every individual coin in the process. People were literally shaving off as much as they could get away with of their silver dollars. I wonder what kind of Dollar Shave Club advertisements they had back in the day.

Since governments are only cool with inflation if they are the ones doing it, efforts were made to stop this guerrilla debasement. In classic cops-and-robbers fashion, coin clippers got ever more creative with their techniques, forcing the ‘masters of the mint’ to get even more creative with their countermeasures. Isaac Newton, the world-renowned physicist of Principia Mathematica fame, used to be one of these masters. He is attributed with adding the small stripes at the side of coins which are still present today. Gone were the days of easy coin shaving.

Even with these methods of coin debasement kept in check, coins still suffer from other issues. They are bulky and not very convenient to transport, especially when large transfers of value need to happen. Showing up with a huge bag of silver dollars every time you want to buy a Mercedes isn’t very practical.

Speaking of German things: How the United States dollar got its name is another interesting story. The word “dollar” is derived from the German word Thaler, short for a Joachimsthaler. A Joachimsthaler was a coin minted in the town of Sankt Joachimsthal. Thaler is simply a shorthand for someone (or something) coming from the valley, and because Joachimsthal was the valley for silver coin production, people simply referred to these silver coins as Thaler. Thaler (German) morphed into daalders (Dutch), and finally dollars (English).

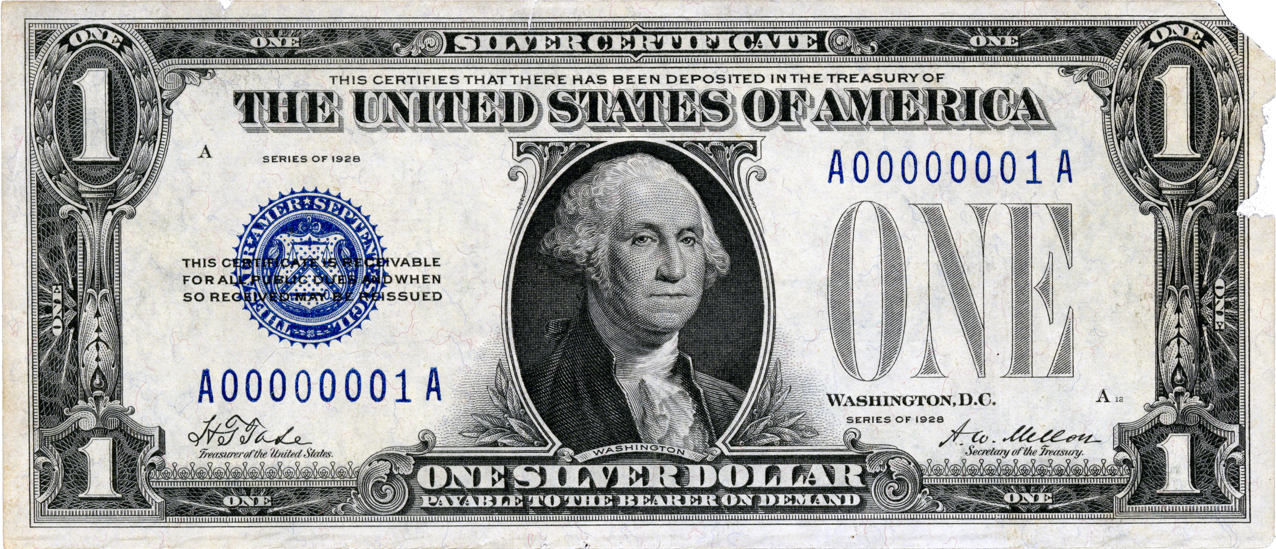

The introduction of representative money heralded the downfall of hard money. Gold certificates were introduced in 1863, and about fifteen years later, the silver dollar was also slowly but surely being replaced by a paper proxy: the silver certificate.

It took about 50 years from the introduction of the first silver certificates until these pieces of paper morphed into something that we would today recognize as one U.S. dollar.

Note that the 1928 U.S. silver dollar above still goes by the name of silver certificate, indicating that this is indeed simply a document stating that the bearer of this piece of paper is owed a piece of silver. It is interesting to see that the text which indicates this got smaller over time. The trace of “certificate” vanished completely after a while, being replaced by the reassuring statement that these are federal reserve notes.

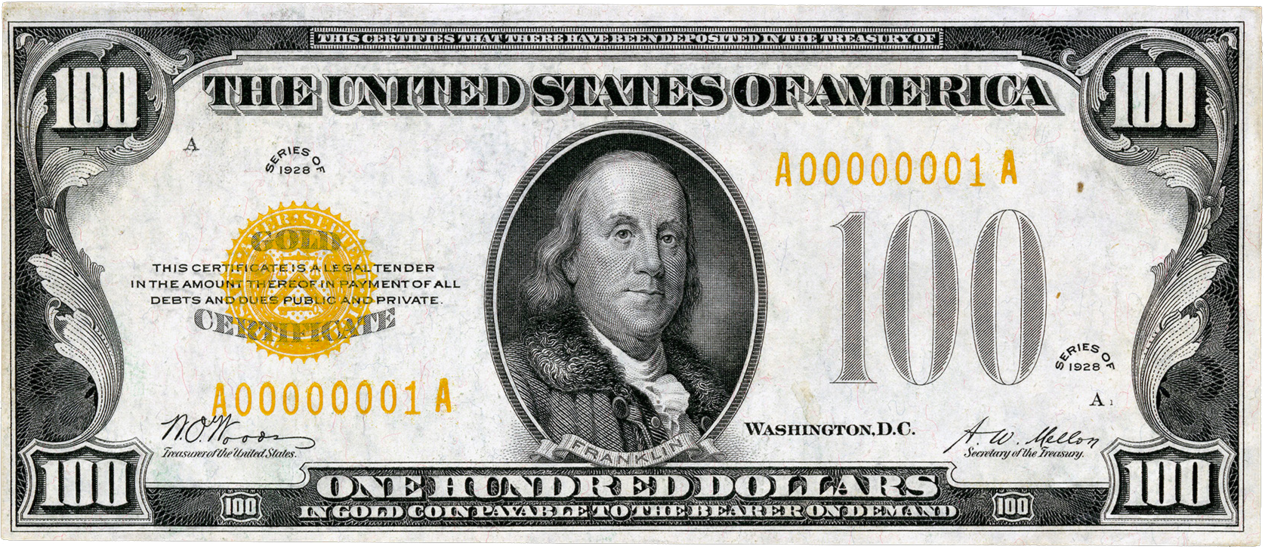

As mentioned above, the same thing happened to gold. Most of the world was on a bimetallic standard, meaning coins were made primarily of gold and silver. Having certificates for gold, redeemable in gold coins, was arguably a technological improvement. Paper is more convenient, lighter, and since it can be divided arbitrarily by simply printing a smaller number on it, it is easier to break into smaller units.

To remind the bearers (users) that these certificates were representative for actual gold and silver, they were colored accordingly and stated this clearly on the certificate itself. You can fluently read the writing from top to bottom:

This certifies that there have been deposited in the treasury of the United States of America one hundred dollars in gold coin payable to the bearer on demand.”

In 1963, the words “PAYABLE TO THE BEARER ON DEMAND” were removed from all newly issued notes. Five years later, the redemption of paper notes for gold and silver ended.

The words hinting on the origins and the idea behind paper money were removed. The golden color disappeared. All that was left was the paper and with it the ability of the government to print as much of it as it wishes.

With the abolishment of the gold standard in 1971, this century-long sleight-of-hand was complete. Money became the illusion we all share to this day: fiat money. It is worth something because someone commanding an army and operating jails says it is worth something. As can be clearly read on every dollar note in circulation today, “THIS NOTE IS LEGAL TENDER”. In other words: It is valuable because the note says so.

By the way, there is another interesting lesson on today’s bank notes, hidden in plain sight. The second line reads that this is legal tender “FOR ALL DEBTS, PUBLIC AND PRIVATE”. What might be obvious to economists was surprising to me: All money is debt. My head is still hurting because of it, and I will leave the exploration of the relation of money and debt as an exercise to the reader.

As we have seen, gold and silver were used as money for millennia. Over time, coins made from gold and silver were replaced by paper. Paper slowly became accepted as payment. This acceptance created an illusion — the illusion that the paper itself has value. The final move was to completely sever the link between the representation and the actual: abolishing the gold standard and convincing everyone that the paper in itself is precious.

Bitcoin taught me about the history of money and the greatest sleight of hand in the history of economics: fiat currency.

Lesson 13: Fractional Reserve Insanity

Value and money aren’t trivial topics, especially in today’s times. The process of money creation in our banking system is equally non-trivial, and I can’t shake the feeling that this is deliberately so. What I have previously only encountered in academia and legal texts seems to be common practice in the financial world as well: nothing is explained in simple terms, not because it is truly complex, but because the truth is hidden behind layers and layers of jargon and apparent complexity. “Expansionary monetary policy, quantitative easing, fiscal stimulus to the economy.” The audience nods along in agreement, hypnotized by the fancy words.

Fractional reserve banking and quantitative easing are two of those fancy words, obfuscating what is really happening by masking it as complex and difficult to understand. If you would explain them to a five-year-old, the insanity of both will become apparent quickly.

Godfrey Bloom, addressing the European Parliament during a joint debate, said it way better than I ever could:

[…] you do not really understand the concept of banking. All the banks are broke. Bank Santander, Deutsche Bank, Royal Bank of Scotland — they’re all broke! And why are they broke? It isn’t an act of God. It isn’t some sort of tsunami. They’re broke because we have a system called ‘fractional reserve banking’ which means that banks can lend money that they don’t actually have! It’s a criminal scandal and it’s been going on for too long. […]

We have counterfeiting — sometimes called quantitative easing — but counterfeiting by any other name. The artificial printing of money which, if any ordinary person did, they’d go to prison for a very long time […] and until we start sending bankers — and I include central bankers and politicians — to prison for this outrage it will continue.”

Let me repeat the most important part: banks can lend money that they don’t actually have.

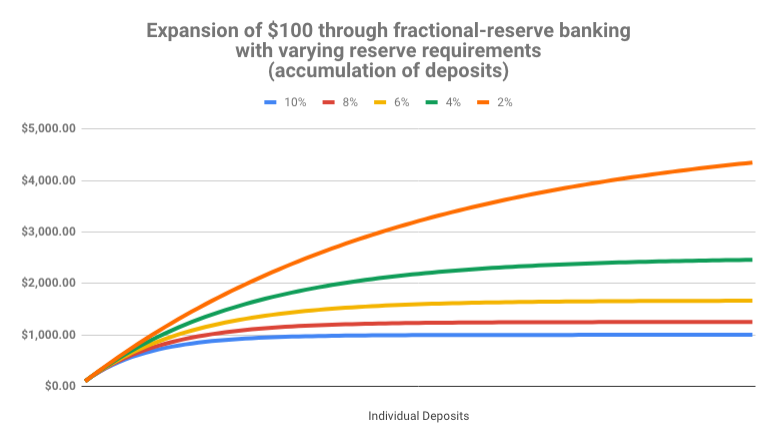

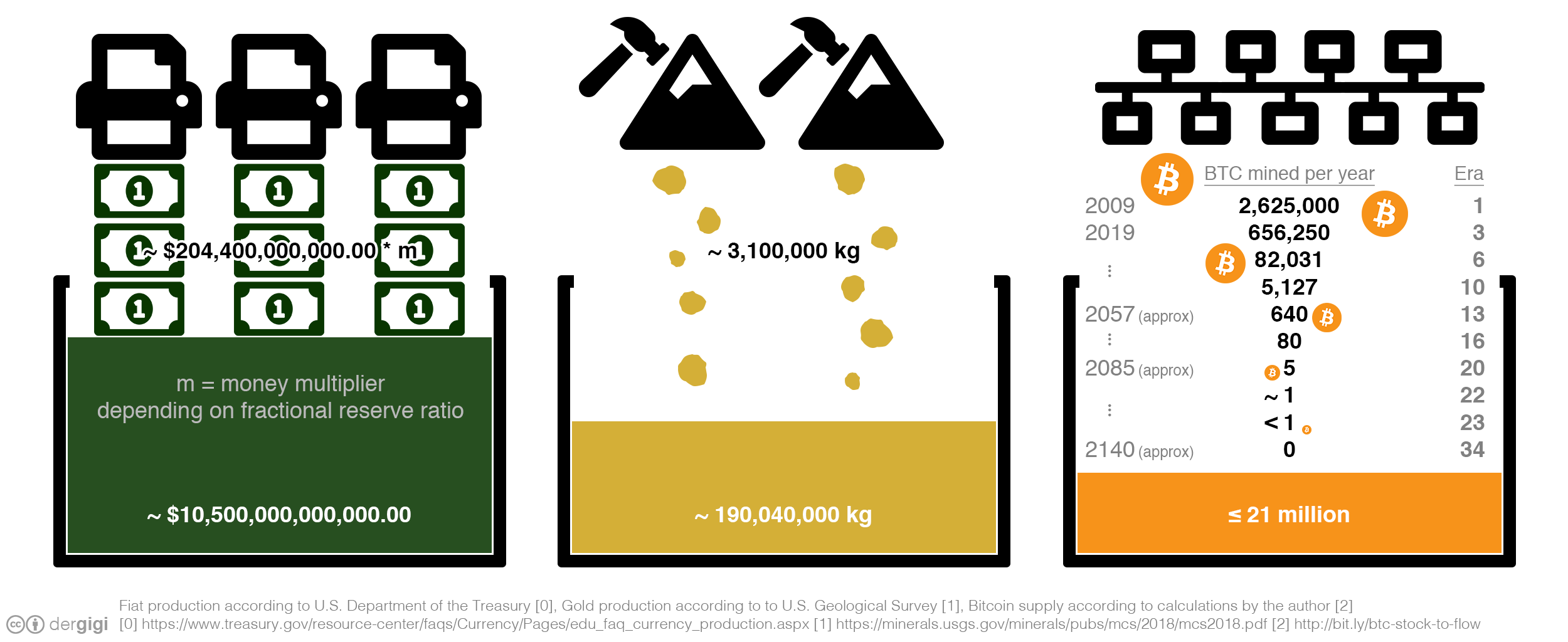

Thanks to fractional reserve banking, a bank only has to keep a small fraction of every dollar it gets. It’s somewhere between 0 and 10%, usually at the lower end, which makes things even worse.

Let’s use a concrete example to better understand this crazy idea: A fraction of 10% will do the trick and we should be able to do all the calculations in our head. Win-win. So, if you take $100 to a bank — because you don’t want to store it under your mattress — they only have to keep the agreed upon fraction of it. In our example that would be $10, because 10% of $100 is $10. Easy, right?

So what do banks do with the rest of the money? What happens to your $90? They do what banks do, they lend it to other people. The result is a money multiplier effect, which increases the money supply in the economy enormously. Your initial deposit of $100 will soon turn into $190. By lending a 90% fraction of the newly created $90, there will soon be $271 in the economy. And $343.90 after that. The money supply is recursively increasing, since banks are literally lending money they don’t have. Without a single Abracadabra, banks magically transform $100 into one thousand dollars or more. Turns out 10x is easy. It only takes a couple of lending rounds.

Don’t get me wrong: There is nothing wrong with lending. There is nothing wrong with interest. There isn’t even anything wrong with good old regular banks to store your wealth somewhere more secure than in your sock drawer.

Central banks, however, are a different beast. Abominations of financial regulation, half public half private, playing god with something which affects everyone who is part of our global civilization, without a conscience, only interested in the immediate future, and seemingly without any accountability or auditability.

While Bitcoin is still inflationary, it will cease to be so rather soon. The strictly limited supply of 21 million bitcoins will eventually do away with inflation completely. We now have two monetary worlds: an inflationary one where money is printed arbitrarily, and the world of Bitcoin, where final supply is fixed and easily auditable for everyone. One is forced upon us by violence, the other can be joined by anyone who wishes to do so. No barriers to entry, no one to ask for permission. Voluntary participation. That is the beauty of Bitcoin.

I would argue that the argument between Keynesian and Austrian economists is no longer purely academical. Satoshi managed to build a system for value transfer on steroids, creating the soundest money which ever existed in the process. One way or another, more and more people will learn about the scam which is fractional reserve banking. If they come to similar conclusions as most Austrians and Bitcoiners, they might join the ever-growing internet of money. Nobody can stop them if they choose to do so.

Bitcoin taught me that fractional reserve banking is pure insanity.

Lesson 14: Sound money

The most important lesson I have learned from Bitcoin is that in the long run, hard money is superior to soft money. Hard money, also referred to as sound money, is any globally traded currency that serves as a reliable store of value.

Granted, Bitcoin is still young and volatile. Critics will say that it does not store value reliably. The volatility argument is missing the point. Volatility is to be expected. The market will take a while to figure out the just price of this new money. Also, as is often jokingly pointed out, it is grounded in an error of measurement. If you think in dollars you will fail to see that one bitcoin will always be worth one bitcoin.

A fixed money supply, or a supply altered only in accord with objective and calculable criteria, is a necessary condition to a meaningful just price of money.”

As a quick stroll through the graveyard of forgotten currencies has shown, money which can be printed will be printed. So far, no human in history was able to resist this temptation.

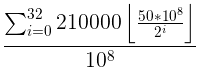

Bitcoin does away with the temptation to print money in an ingenious way. Satoshi was aware of our greed and fallibility — this is why he chose something more reliable than human restraint: mathematics.

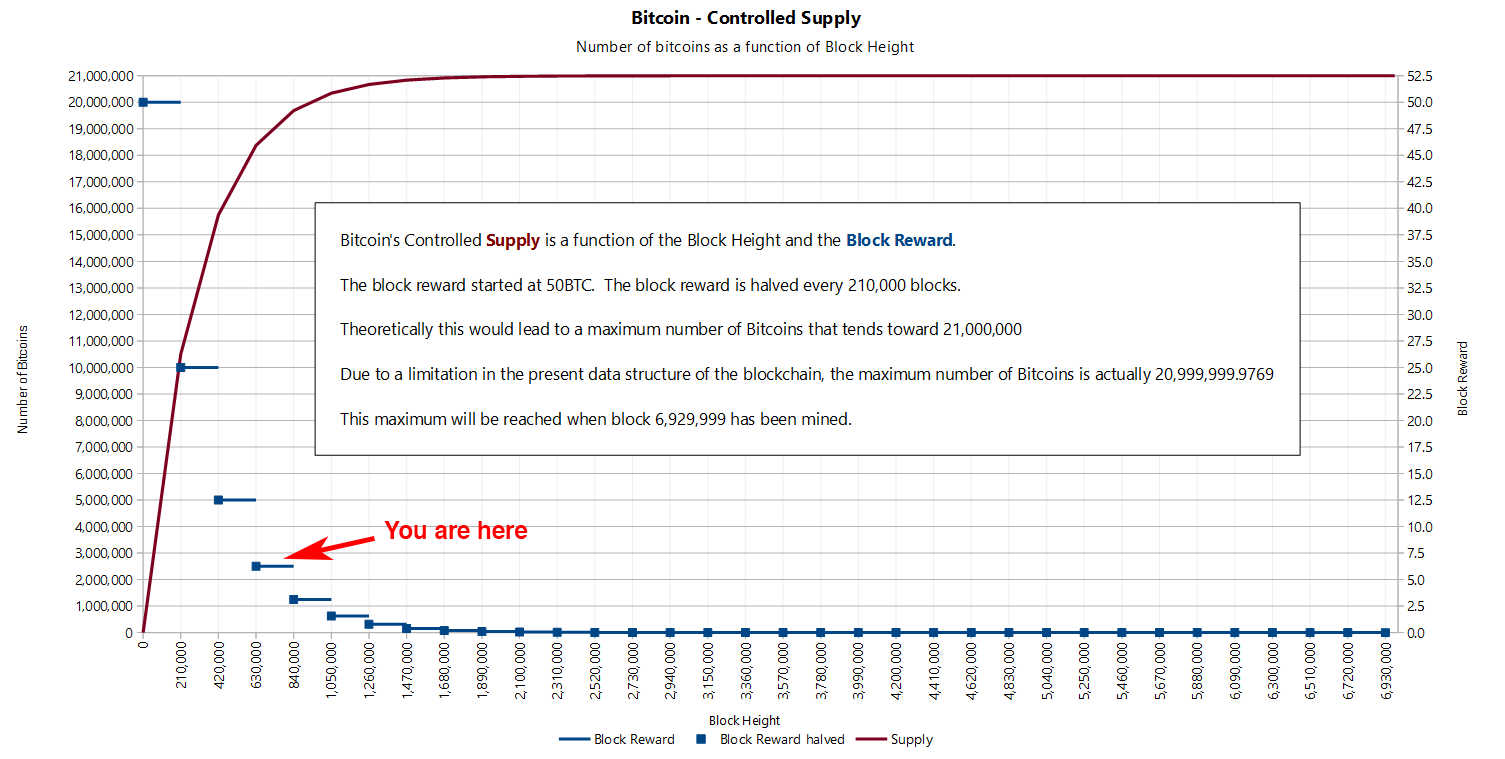

While this formula is useful to describe Bitcoin’s supply, it is actually nowhere to be found in the code. Issuance of new bitcoin is done in an algorithmically controlled fashion, by reducing the reward which is paid to miners every four years. The formula above is used to quickly sum up what is happening under the hood. What really happens can be best seen by looking at the change in block reward, the reward paid out to whoever finds a valid block, which roughly happens every 10 minutes.

Formulas, logarithmic functions and exponentials are not exactly intuitive to understand. The concept of soundness might be easier to understand if looked at in another way. Once we know how much there is of something, and once we know how hard this something is to produce or get our hands on, we immediately understand its value. What is true for Picasso’s paintings, Elvis Presley’s guitars, and Stradivarius violins is also true for fiat currency, gold, and bitcoins.

The hardness of fiat currency depends on who is in charge of the respective printing presses. Some governments might be more willing to print large amounts of currency than others, resulting in a weaker currency. Other governments might be more restrictive in their money printing, resulting in harder currency.

Before we had fiat currencies, the soundness of money was determined by the natural properties of the stuff which we used as money. The amount of gold on earth is limited by the laws of physics. Gold is rare because supernovae and neutron star collisions are rare. The “flow” of gold is limited because extracting it is quite an effort. Being a heavy element it is mostly buried deep underground.

The abolishment of the gold standard gave way to a new reality: adding new money requires just a drop of ink. In our modern world adding a couple of zeros to the balance of a bank account requires even less effort: flipping a few bits in a bank computer is enough.

One important aspect of this new reality is that institutions like the Fed cannot go bankrupt. They can print any amount of money that they might need for themselves at virtually zero cost.”

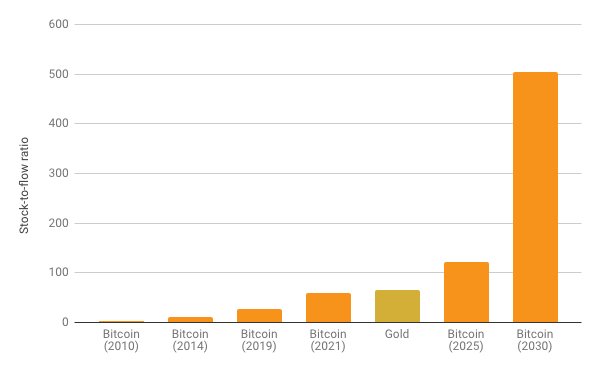

The principle outlined above can be expressed more generally as the ratio of “stock” to “flow”. Simply put, the stock is how much of something is currently there. For our purposes, the stock is a measure of the current money supply. The flow is how much there is produced over a period of time (e.g. per year). The key to understanding sound money is in understanding this stock-to-flow ratio.

Calculating the stock-to-flow ratio for fiat currency is difficult, because how much money there is depends on how you look at it. You could count only banknotes and coins (M0), add traveler checks and check deposits (M1), add saving accounts and mutual funds and some other things (M2), and even add certificates of deposit to all of that (M3). Further, how all of this is defined and measured varies from country to country and since the US Federal Reserve stopped publishing numbers for M3, we will have to make do with the M2 monetary supply. I would love to verify these numbers, but I guess we have to trust the fed for now.

Gold, one of the rarest metals on earth, has the highest stock-to-flow ratio. According to the US Geological Survey, a little more than 190,000 tons have been mined. In the last few years, around 3100 tons of gold have been mined per year.

Using these numbers, we can easily calculate the stock-to-flow ratio for gold: 190,000 tons / 3,100 tons = ~61.

Nothing has a higher stock-to-flow ratio than gold. This is why gold, up to now, was the hardest, soundest money in existence. It is often said that all the gold mined so far would fit in two olympic-sized swimming pools. According to my calculations, we would need four. So maybe this needs updating, or Olympic-sized swimming pools got smaller.

Enter Bitcoin. As you probably know, bitcoin mining was all the rage in the last couple of years. This is because we are still in the early phases of what is called the reward era, where mining nodes are rewarded with a lot of bitcoin for their computational effort. We are currently in reward era number 3, which began in 2016 and will end in early 2020, probably in May. While the bitcoin supply is predetermined, the inner workings of Bitcoin only allow for approximate dates. Nevertheless, we can predict with certainty how high Bitcoin’s stock-to-flow ratio will be. Spoiler alert: it will be high.

How high? Well, it turns out that Bitcoin will get infinitely hard.

Due to an exponential decrease of the mining reward, the flow of new bitcoin will diminish resulting in a sky-rocketing stock-to-flow ratio. It will catch up to gold in 2020, only to surpass it four years later by doubling its soundness again. Such a doubling will occur 64 times in total. Thanks to the power of exponentials, the number of bitcoin mined per year will drop below 100 bitcoin in 50 years and below 1 bitcoin in 75 years. The global faucet which is the block reward will dry up somewhere around the year 2140, effectively stopping the production of bitcoin. This is a long game. If you are reading this, you are still early.

As bitcoin approaches infinite stock to flow ratio it will be the soundest money in existence. Infinite soundness is hard to beat.

Viewed through the lens of economics, Bitcoin’s difficulty adjustment is probably its most important component. How hard it is to mine bitcoin depends on how quickly new bitcoins are mined*. It is the dynamic adjustment of the network’s mining difficulty which enables us to predict its future supply.

(* It actually depends on how quickly valid blocks are found, but for our purposes, this is the same thing as “mining bitcoins” and will be so for the next 120 years.)

The simplicity of the difficulty adjustment algorithm might distract from its profundity, but the difficulty adjustment truly is a revolution of Einsteinian proportions. It ensures that, no matter how much or how little effort is spent on mining, Bitcoin’s controlled supply won’t be disrupted. As opposed to every other resource, no matter how much energy someone will put into mining bitcoin, the total reward will not increase.

Just like E=mc² dictates the universal speed limit in our universe, Bitcoin’s difficulty adjustment dictates the universal money limit in Bitcoin.

If it weren’t for this difficulty adjustment, all bitcoins would have been mined already. If it weren’t for this difficulty adjustment, Bitcoin probably wouldn’t have survived in its infancy. It is what secures the network in its reward era. It is what ensures a steady and fair distribution of new bitcoin. It is the thermostat which regulates Bitcoin’s monetary policy.

Einstein showed us something novel: no matter how hard you push an object, at a certain point you won’t be able to get more speed out of it. Satoshi also showed us something novel: no matter how hard you dig for this digital gold, at a certain point you won’t be able to get more bitcoin out of it. For the first time in human history, we have a monetary good which, no matter how hard you try, you won’t be able to produce more of.

Bitcoin taught me that me that sound money is essential.

Conclusion

As we leave the “blockchain not bitcoin” days behind us, most people start to realize that there is not a single invention which encapsulates the genius of Bitcoin. It is the combination of multiple, previously unrelated pieces, glued together by game theoretical incentives, which make up the revolution that is Bitcoin.

For me, the economic teachings of Bitcoin are as fascinating as the philosophical ones examined in part one. Being a technophile, I can’t wait to tell you what Bitcoin taught me about technology in the third and final part of this series.

As mentioned before, I think that any answer to the question “What have you learned from Bitcoin?” will always be incomplete. The symbiosis of the two living systems examined here — Bitcoin and economics — is too intertwined and evolving too fast to ever be fully understood by a single person.

“I don’t believe we shall ever have a good money again before we take the thing out of the hands of government, that is, we can’t take it violently out of the hands of government, all we can do is by some sly roundabout way introduce something that they can’t stop.”

Learning these lessons enabled me to finally understand what Hayek meant by the above. I believe that Bitcoin is the sly, roundabout way to re-introduce sound money to the world. Thanks to the economic teachings of Bitcoin I learned what good money is and that having it is possible.

What have you learned from Bitcoin?

Acknowledgments

- Again, thanks to Arjun Balaji for the tweet which gave birth to this series.

- Thanks to Saifedean Ammous for his convictions, savage tweets, and writing The Bitcoin Standard

- Thanks to Dhruv Bansal for taking the time to discuss some of these ideas with me.

- Thanks to Matt Odell for his candor and also for taking the time to discuss some of these ideas with me, even if he doesn’t remember all of it.

- Thanks to Michael Goldstein and Pierre Rochard for curating and providing relevant literature via the Nakamoto Institute

- Thanks to Jannik, Camilo, and Matt for providing feedback to early drafts of this article

Further Reading

There exists an almost endless list of books and essays on the topics discussed above and economic thought in general. The books and articles listed below are but a small selection which were particularly influential in my thinking. I am grateful for all the people who shared their insights, past and present.

- The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking by Saifedean Ammous

- Economics in One Lesson by Henry Hazlitt

- Human Action by Ludwig von Mises

- The Ethics of Money Production by Jörg Guido Hülsmann

- The Denationalization of Money by Friedrich Hayek

- The Machinery of Freedom by David D. Friedman

- The Case Against The Fed by Murray N. Rothbard

- End the Fed by Ron Paul

- Shelling Out: The Origins of Money by Nick Szabo

- The Bitcoin Halving and Monetary Competition by Saifedean Ammous

- The Bullish Case For Bitcoin by Vijay Boyapati

- Bitcoin’s distribution was fair by Dan Held

🧡

Found this valuable? Don't have sats to spare? Consider sharing it, translating it, or remixing it.Confused? Learn more about the V4V concept.